In a quiet operating room at the University of Michigan, a team of neurosurgeons made history. For the first time, a patient undergoing epilepsy surgery had a brain-computer interface (BCI) device, called the Connexus, implanted and removed in a swift 20-minute procedure. This milestone marks a bold step forward in the quest to connect human brains directly to computers.

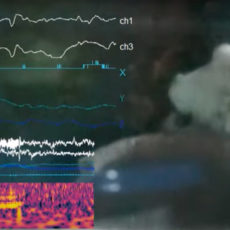

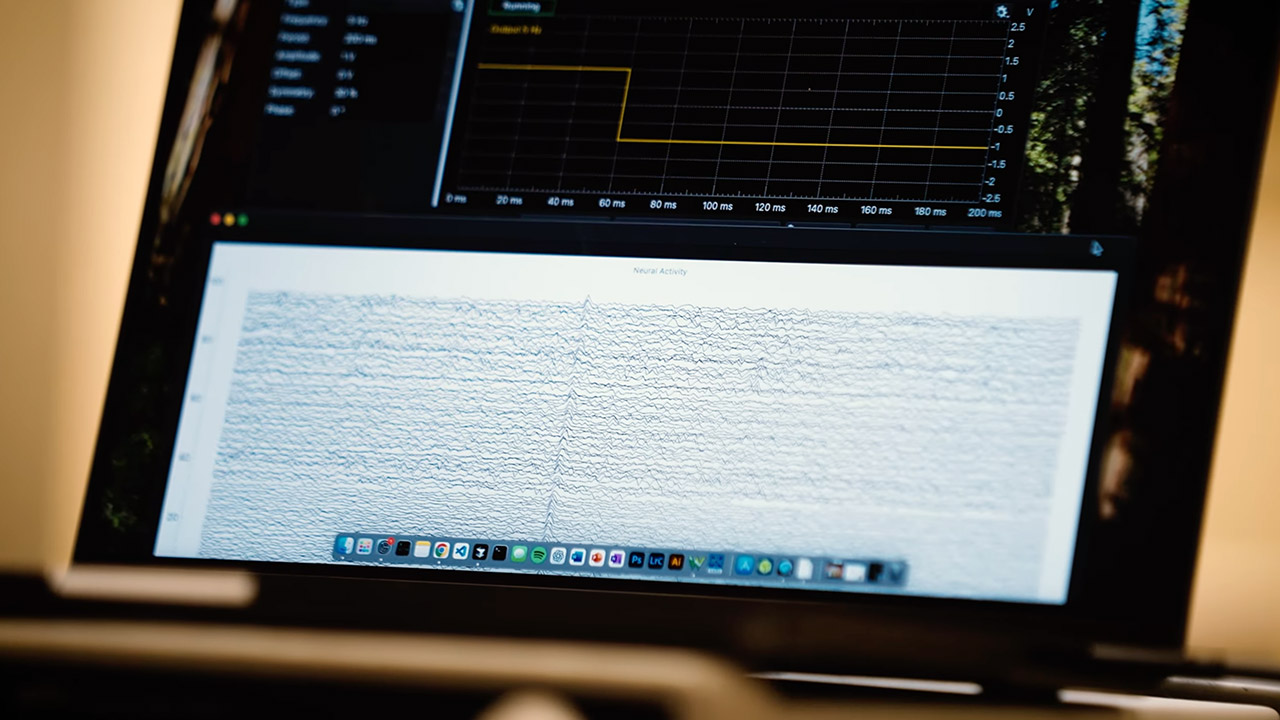

This wasn’t a permanent implant, but rather a proof-of-concept, or a quick test drive to show the device could safely sit in a human brain and capture neural signals. The patient, already undergoing surgery to treat epilepsy, consented to having the Connexus briefly placed in their temporal lobe, a region critical for processing sound and memory. In those fleeting minutes, the device’s 100 spikelike electrodes recorded electrical activity from individual neurons, offering a glimpse of what’s possible when technology listens to the brain’s whispers. “It’s absolutely thrilling,” said Dr. Matthew Willsey, the neurosurgeon who led the procedure. “It’s motivating, and this is the kind of thing that helps me get up in the morning and go to work.”

- Transform your reality and do everything you love in totally new ways. Welcome to Meta Quest 3S. Now you can get the Batman: Arkham Shadow* and a...

- Explore thousands of unreal experiences with mixed reality, where you can blend digital objects into the room around you or dial up the immersion in...

- Have more fun with friends in Quest. Whether you’re stepping into an immersive game with people from around the world, watching a live concert...

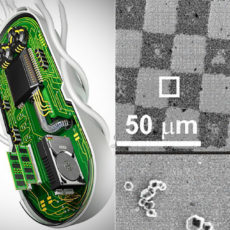

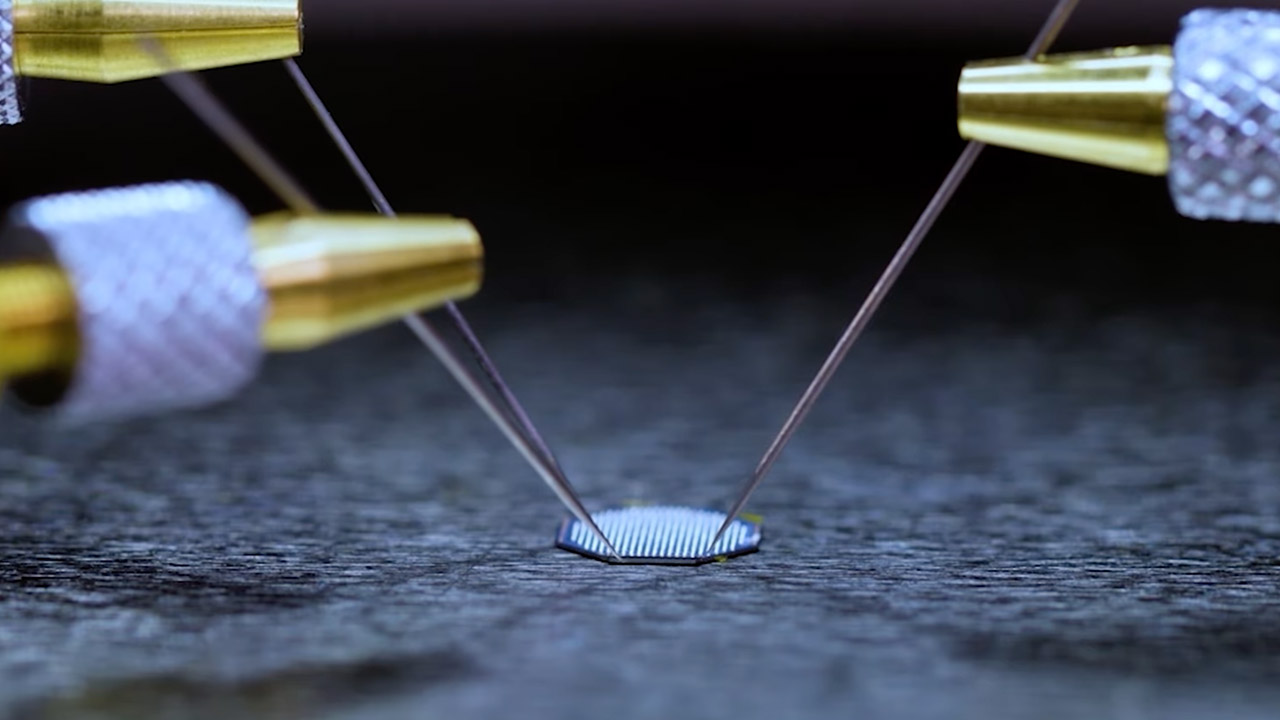

Paradromics’ Connexus is designed to do what sounds almost magical: translate the brain’s electrical chatter into actions like typing, moving a cursor, or even speaking through synthesized speech. For people with severe motor impairments—those with spinal cord injuries, stroke, or ALS who can no longer speak or move—the goal is to restore their ability to communicate. The device works by placing a small, hairbrush-like module on the brain’s surface, where its tiny electrodes, thinner than a human hair, pick up signals from individual neurons. These signals travel through a flexible lead to a chest-implanted transceiver, which wirelessly sends data to a computer. There, advanced AI decodes the neural patterns into meaningful outputs, like text or speech.

The patient wasn’t there specifically for the BCI; they were already having brain surgery. “There’s a very unique opportunity when someone is undergoing a major neurosurgical procedure,” said Matt Angle, CEO of Paradromics. “They’re going to have their skull opened up, and there’s going to be a piece of brain that will be imminently removed. Under these conditions, the marginal risk of testing out a brain implant is actually very low.”

Neuralink, backed by Elon Musk, has grabbed headlines with its own human implants, aiming to push the boundaries of brain augmentation. Synchron, supported by Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, focuses on less invasive approaches, placing devices in blood vessels rather than directly in brain tissue. Paradromics, however, is carving its niche with a focus on high-resolution data. Angle likens their approach to placing microphones inside a stadium to capture individual conversations, rather than outside to hear only the crowd’s roar. With up to 1,681 electrodes across multiple modules, the Connexus could collect far more detailed neural data than competitors, potentially enabling faster, more natural communication—like decoding speech at rates approaching normal conversation, around 130 words per minute.

The Connexus still needs FDA clearance, and the planned 2025 clinical trial will focus on patients with ALS, stroke, or spinal cord injuries. The study, led by investigators Dr. David Brandman and Dr. Daniel Rubin, will assess not just safety but also how well the device restores communication and improves quality of life. “For people unable to communicate due to motor impairment, there is significant unmet medical need,” Rubin said. “I look forward to exploring how rich, high-bandwidth brain data can produce real-time, accurate communication.” Brandman echoed the excitement: “This research is an important step for the field of BCI technology, investigating how BCI users can communicate through synthesized speech and text.”