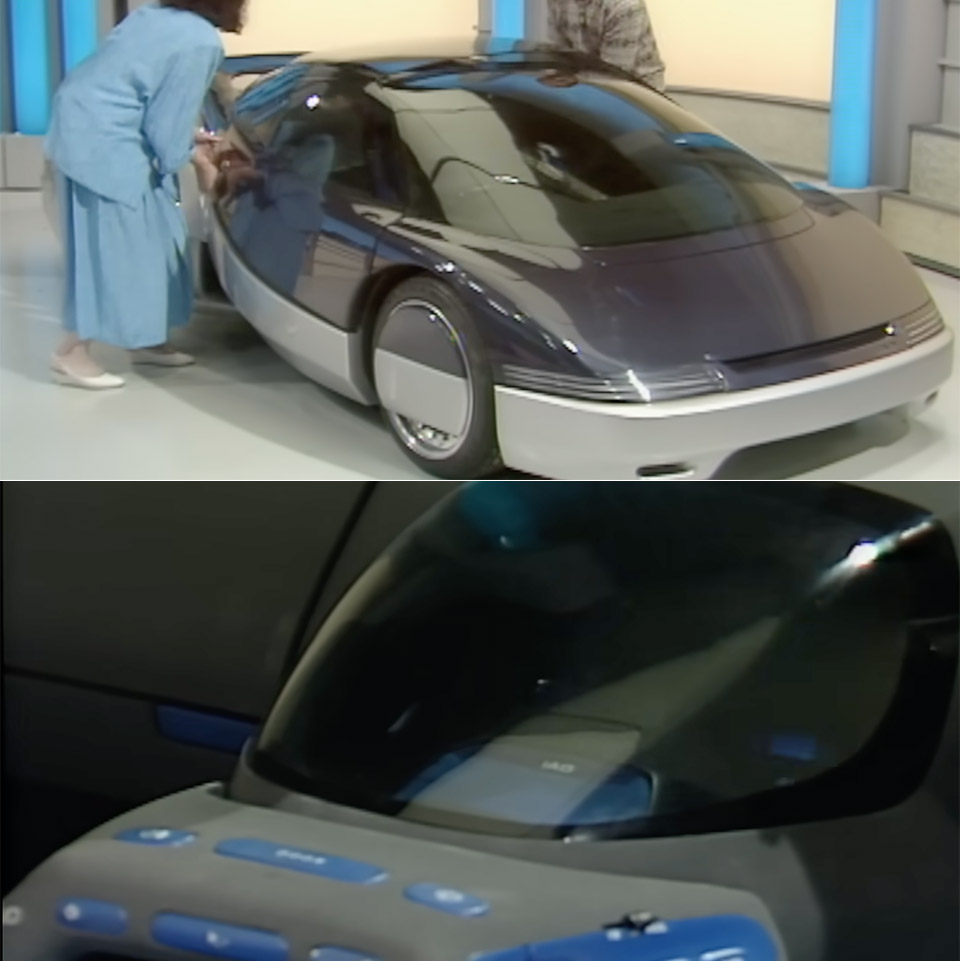

In a 1986 broadcast of the BBC’s Tomorrow’s World, hosts Judith Hann and Peter Macann show off a concept car that’s a time capsule of ambition. We get to see what the car makers and researchers thought the 21st century would be like – a dashboard screen instead of instruments and a satellite navigation system that would guide you effortlessly.

Peter Macann calls it his own, but it’s clearly a prototype to test new ideas. Inside, the lack of analogue dials is striking. A glowing screen dominates the dashboard, showing information and being the interface for a satellite navigation system. This was simple by today’s standards but innovative in 1986. The system uses satellite signals to plot the route, to reduce navigation stress.

- Wireless Carplay and Android Auto: This plug-and-play 9-inch carplay screen for car supports both Android Android Auto and Carplay, so it's easy to...

- Real-time GPS Navigation with Voice Control: The portable carplay screen provides precise real-time location and GPS navigation without delay. Allows...

- Front 4K DVR Loop Recording Camera & 1080p Night Vision Backup Camera: The car screen equipped with a front 4K camera and 1080P waterproof reversing...

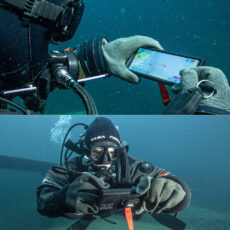

Maggie Philbin visits Crowthorne and the focus moves to practical testing. She gets into a car that looks like a normal one, but houses a cutting edge prototype inside. A computer with bubble memory – a quirky, now obsolete storage technology – is in the boot, storing a digital map. The computer calculates the car’s position and tells the driver based on direction and distance travelled. Philbin types in her start and end point and a synthesized voice says “Turn left onto the A3095”. It’s a clumsy system that requires manual input and a static map that doesn’t account for new roads or traffic jams. Drivers in 1986 used to paper maps and guessing, find this magic.

Not everyone in the research lab agrees with this approach. The bubble memory technology is innovative but not without problems. The map is stuck in time and becomes obsolete the moment a new road is built. It can’t reroute around accidents or construction, a major drawback in a world where traffic jams are everyday. Crowthorne researchers are already looking into other solutions and Philbin is testing another version in a Range Rover. This technology replaces onboard maps with roadside computers. Drivers enter a code (Windsor in this case) and a radio transmitter behind the number plate talks to loops in the road. These loops send signals to a roadside computer which returns directions like “A355, turn right”. It’s a more dynamic system that can update the route in real time.

The Range Rover system is clever. Philbin explains how it works as she drives a simulated journey across Oxford. Roadside computers track traffic flow, including how long it takes to get from one junction to another. If a pileup delays her on the A40 the system alerts a central computer which modifies the routes for other drivers. Instead of taking the congested ring road the system might advise cutting through the city centre on the A420. This real time response feels like a game changer, a future where cars and infrastructure talk to each other. Is there a catch? The roadside computers are expensive and the section raises an important question: who pays the bill?