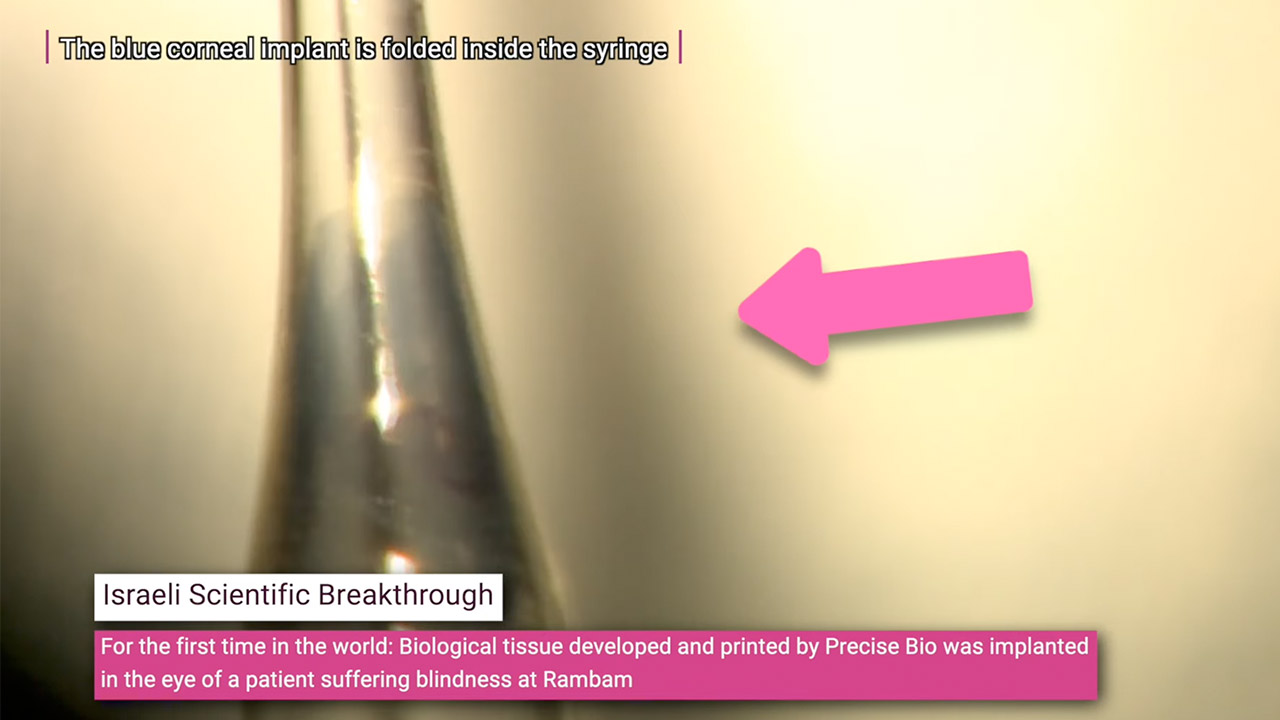

In the soft glow of the operating room at Rambam Medical Center in Haifa, Israel, Dr. Michael Mimouni locked in a moment of suspense that would be remembered for a lot longer than the time he spent in that room. October was rolling into November in 2025, and on the 29th, his team accomplished something incredible: the world’s first transplant of a fully 3D-printed corneal implant manufactured from actual living human cells.

The patient, a 70-year-old woman who had lost sight in one eye due to a severe case of corneal disease, walked away with her vision restored. And she did it without the need for a donor; the technician utilized lab-grown cells to complete the procedure. Years of darkness were transformed into a sharp and familiar new reality.

- High-Speed Precision: Experience unparalleled speed and precision with the Bambu Lab A1 Mini 3D Printer. With an impressive acceleration of 10,000...

- Multi-Color Printing with AMS lite: Unlock your creativity with vibrant and multi-colored 3D prints. The Bambu Lab A1 Mini 3D printers make...

- Full-Auto Calibration: Say goodbye to manual calibration hassles. The A1 Mini 3D printer takes care of all the calibration processes automatically,...

Corneal issues appear and disappear out of nowhere. Infections, accidents, and hereditary disorders can all damage the cornea, which can enlarge and cause blindness. In places with well established eye banks like the US, patients often get the help they need within weeks and the success rate is a pretty impressive 97%. But elsewhere the waiting game can drag on for years or even never end at all. Traditional transplant surgery involves replacing the injured piece with one donated by a deceased person, a delicate switch that requires a great deal of expertise and a little luck. You remove the faulty component, insert the new one, sew or press it into place, and hope for the best. The recovery process takes months, and there is always the possibility of rejection or infection, but when all goes well, patients can see a world of color they had forgotten and even enjoy simple things like being able to read the sign outside the shop.

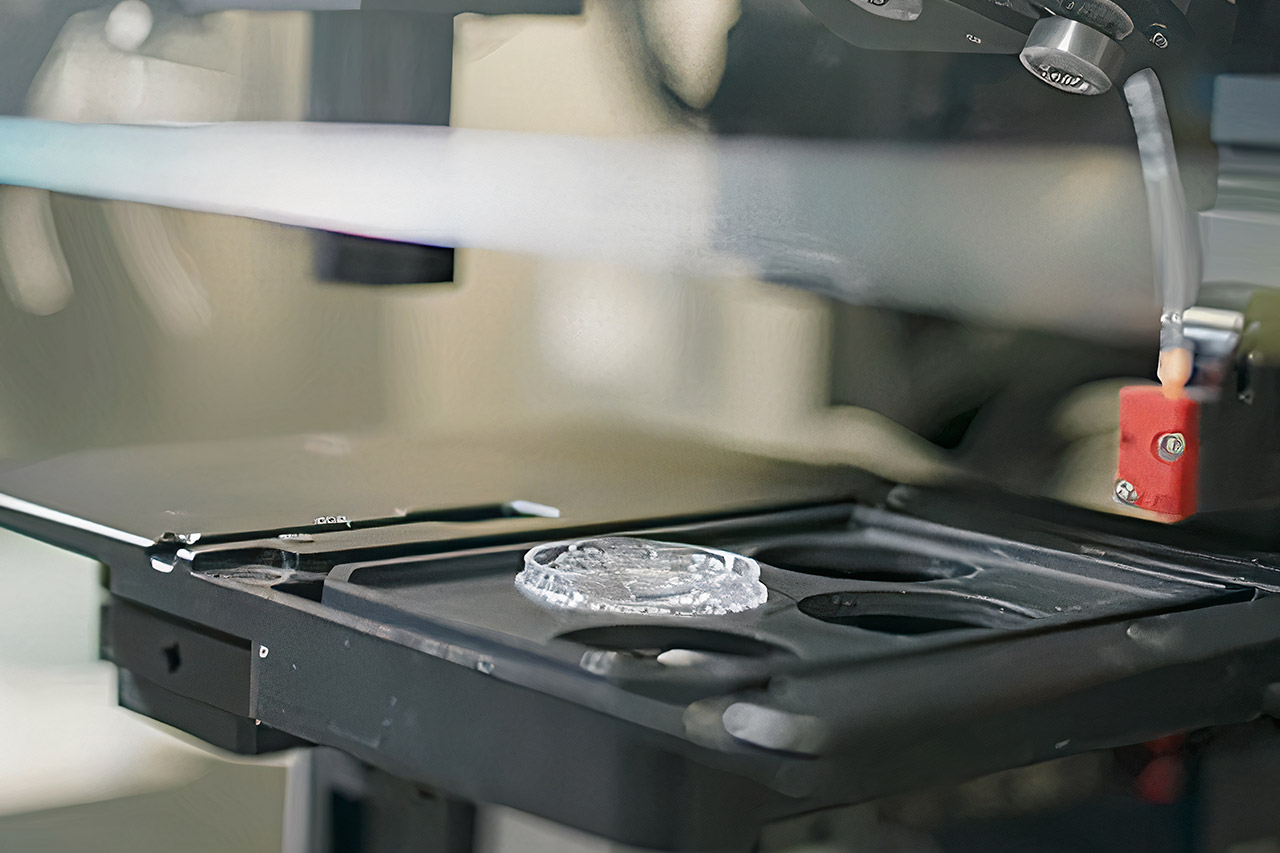

It all began seven years ago with a sall experiment at a university lab in Newcastle. The researchers first got their heads around the idea of layering human corneal cells into a printed structure that could maintain its form and clarity. And that’s when it began to snowball: a relationship with Precise Bio, a North Carolina business that spent the next decade improving the method. They developed a technique based on a 3D printer, similar to those used to make houses out of concrete, except this one works with live elements. You begin with a single healthy cornea, extract the particular cells that pump the moisture out so the eye does not become too soggy, multiply them, and then feed the mixture into the printer, which lays down layers of collagen, a natural substance found in our bodies. And just like that, you have the five layers of the cornea: tough outer skin, a little of watery middle, and the all-important pump. One healthy donor can help 300 people regain their sight.

Mimouni and his colleagues at the Rambam Eye Institute chose this woman to be the first to try the new procedure because her case was a perfect fit; her problem was endothelial dysfunction, which meant that the inner cells of her eye had begun to fail and fluid was building up behind them, causing her to be able to see only the outline of shapes. At this time, she had almost no vision in that eye, and her world was a jumble of dark shadows. The surgery was essentially a typical transplant procedure, but with an interesting twist: using a microscope, the team gently peeled back the layers of scarring before inserting the custom-built implant, which was approximately the size of a contact lens, directly into the exposed surface. The body’s natural forces maintain it in place, and the whole procedure was over in less than an hour.

The swelling subsided over months, and her vision improved. By early November, when word of the procedure finally spread, reports were trickling in that her vision had improved to the point that she could walk around without assistance. There was no sign of rejection, which is a major concern when using foreign tissue. The implant had just seamlessly blended into her system, its cells pulsating in time with the eye’s normal pumping movement. Mimouni, who led the surgery, was ecstatic: “For the first time in history, we’ve seen a lab-created cornea formed from living human cells restore someone’s sight.”

Aryeh Batt, the chief of Precise Bio, has been keeping a close eye on the trial. His team was working on the implant at a unit within the Sheba Medical Centre, a large Israeli hospital. They ensured that each layer of the implant matched the greatest medical requirements. “This milestone is the result of more than a decade of work in cell biology, materials, and 3D printing,” Batt said. The great thing about this technology was that it scales up in a manner that human donor corneas cannot. Imagine factories cranking out corneas on demand, each one fitted to a patient’s exact curvature and thickness, owing to scans input into the printer. The first tests reveal that these lab copies are just as strong and effective at allowing light through as the genuine thing, and they bend the light just so to focus on the retina.

[Source]