A gas station pump computer sits quietly hidden away in a metal cabinet, processing transactions day after day, as most cars go right by without a second thought. Dave from Usagi Electric discovered one of these often-forgotten machines at a swap market and transformed it into a crazy adventure of reverse engineering. The end product is a look at 80s industrial technology that still works decades later.

This system was introduced around 1993, however its origins can be traced back to the 1980s. Gilbarco most likely designed it as a forecourt controller, which is the brain that coordinates all of the gas pumps and point-of-sale systems of a gas station. Rather than having a single chip inside each pump, the entire system is structured around a modular rack of circuit boards that are all connected via a VME backplane. It has six slots for additional components, and the power rails are designed to provide steady voltages even after years of use.

- SIZE DOWN. POWER UP — The far mightier, way tinier Mac mini desktop computer is five by five inches of pure power. Built for Apple Intelligence.*...

- LOOKS SMALL. LIVES LARGE — At just five by five inches, Mac mini is designed to fit perfectly next to a monitor and is easy to place just about...

- CONVENIENT CONNECTIONS — Get connected with Thunderbolt, HDMI, and Gigabit Ethernet ports on the back and, for the first time, front-facing USB-C...

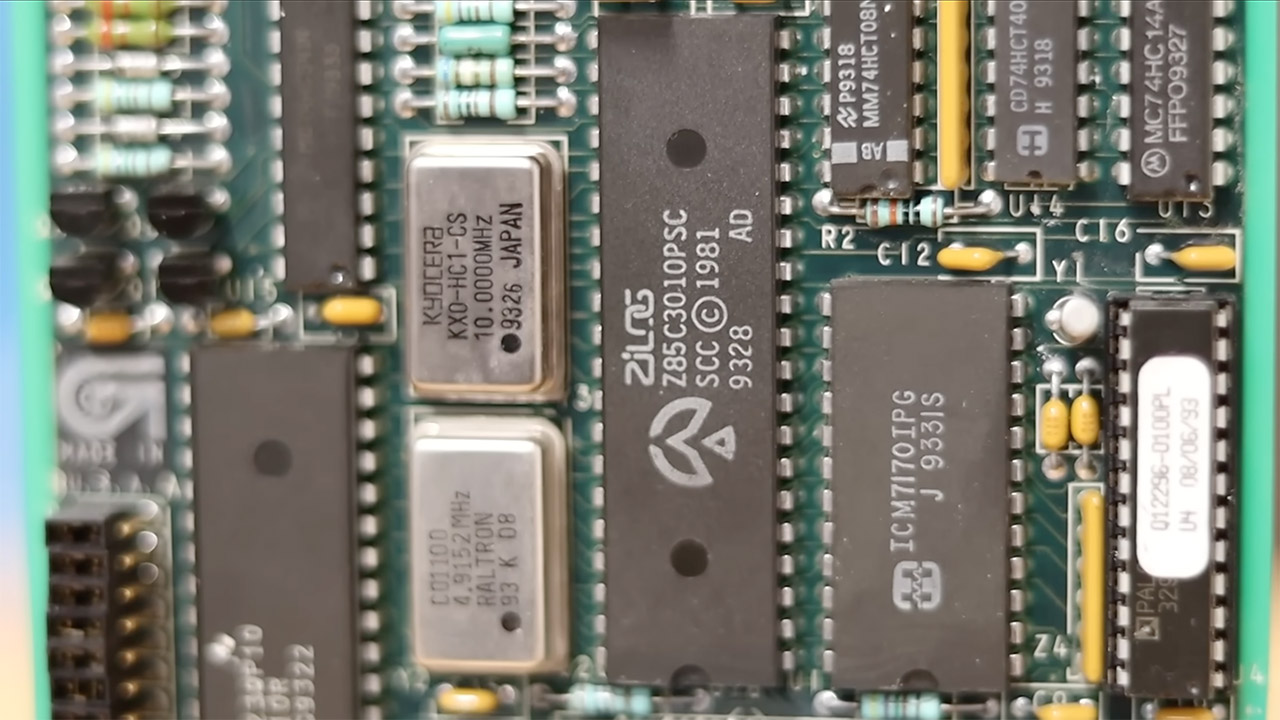

The Motorola MC68HC000FN processor serves as the brain of the operation. This 16/32-bit processor is far more powerful than is required for simple pump logic, but it was a powerhouse back then. There are also a number of support chips around it, such as a parallel interface timer, a Zilog dual serial communications controller, and a real-time clock chip that keeps track of the date, time, and even leap years. There are oscillators keeping everything running at the correct frequencies, one at 10 MHz for the CPU and another at around 4.9 MHz for serial communications.

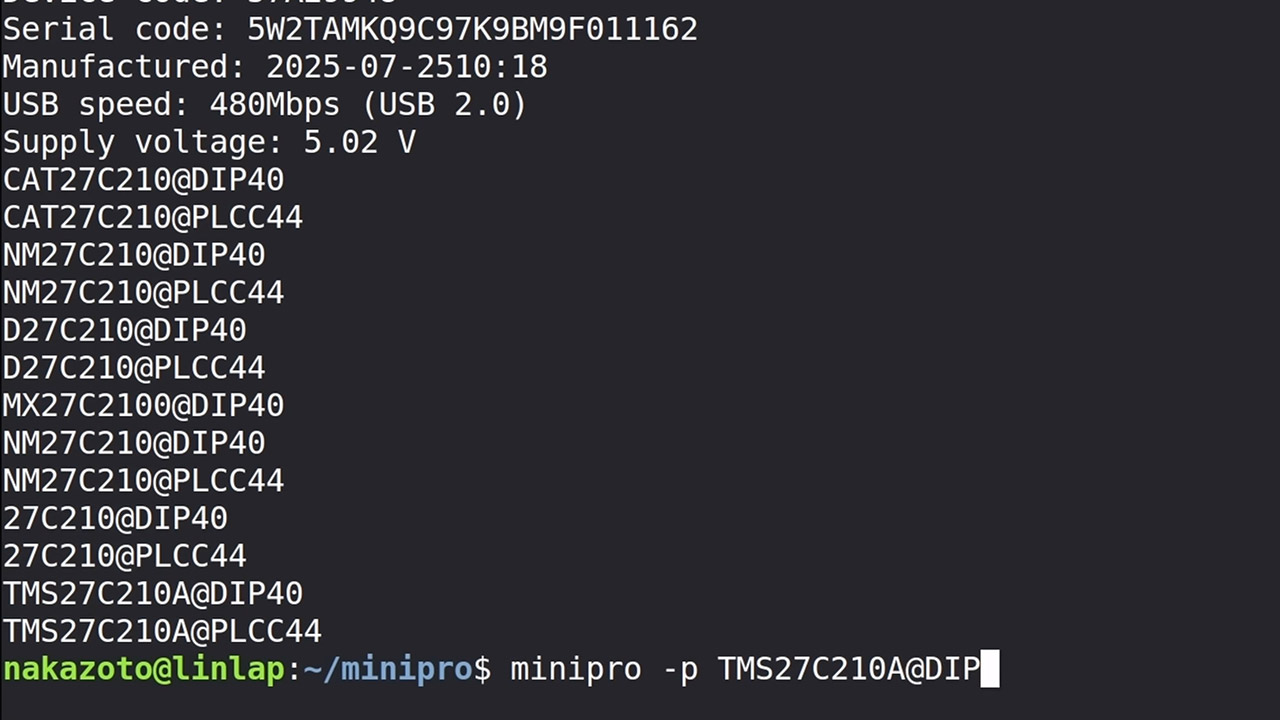

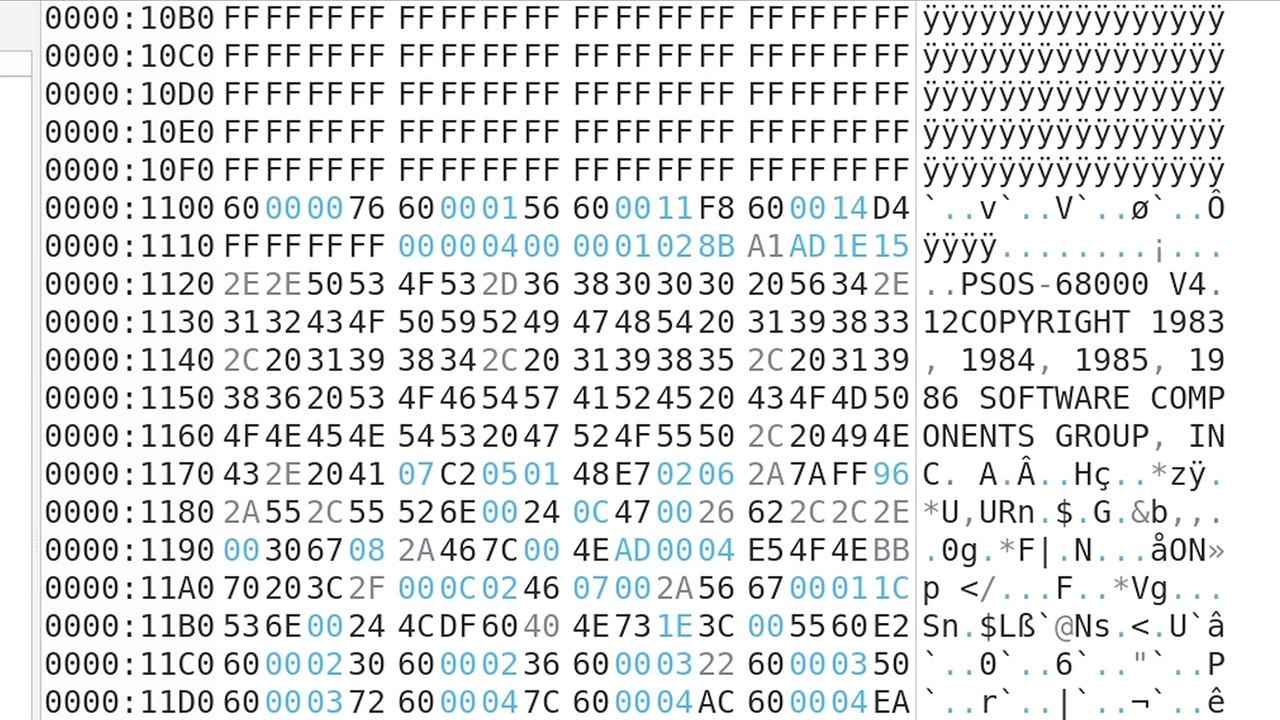

The memory is housed on a separate card, which has three 27C210 EPROMs that store the firmware and total 384 KB. That was a lot of working RAM for an embedded controller back then. There are a few programmable logic devices and bus transceivers that connect everything together. However, one of the capacitors on this board is getting old, and there is a possibility that it will begin to leak over time, an old electronics problem that is all too prevalent.

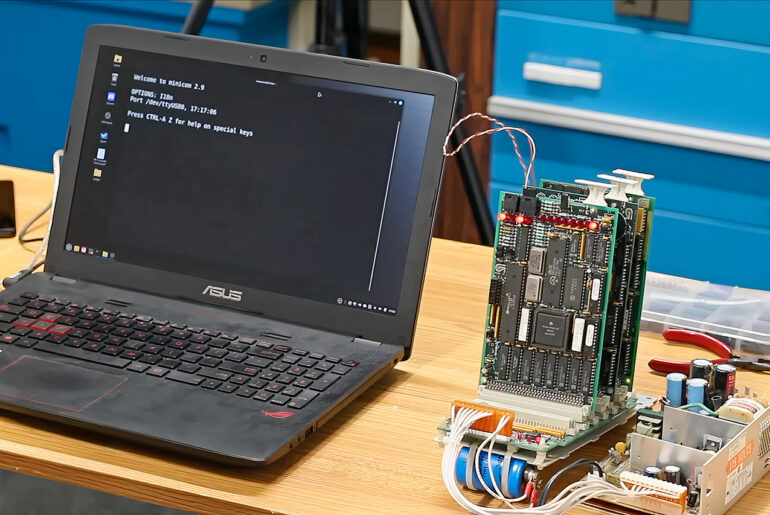

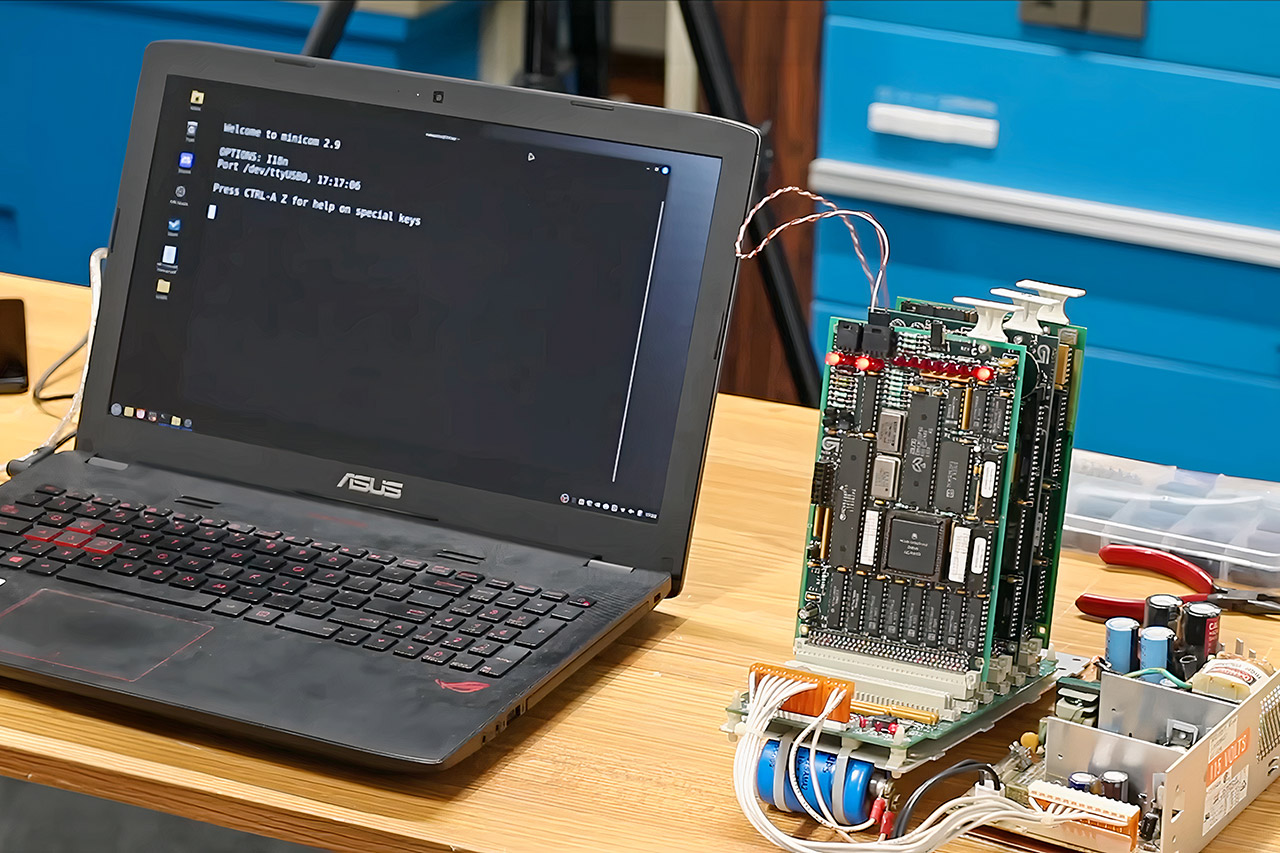

There are two extra serial cards stuffed in there to expand the connectivity, each carrying two Z85C3010 chips, giving you four serial ports per card for a total of eight, but when you’re actually running the comms, it’s over RS-485 twisted pair, a choice built for noise resistance across long distances. The jumpers on the cards allow you to configure various options, but you’ll have to dive deep to figure out what they’re supposed to do. The power supply is a switch-mode unit from the early 1980s that provides +5V at 6A, +12V at 2.5A, and various smaller rails for isolated circuitry. There are large capacitors smoothing out the output, and even after years of storage, it still produces clean voltages.

Firmware lies in those EPROMs that run pSOS, a very old Real-time operating system from the 1980s. The moniker “Portable Software On Silicon” remained because it fit so well on embedded processors like the 68000 family. This small operating system is all about getting the timing correct for tasks like pump authorization, fuel flow monitoring, transaction logging, and communication with payment terminals as well as central station systems.

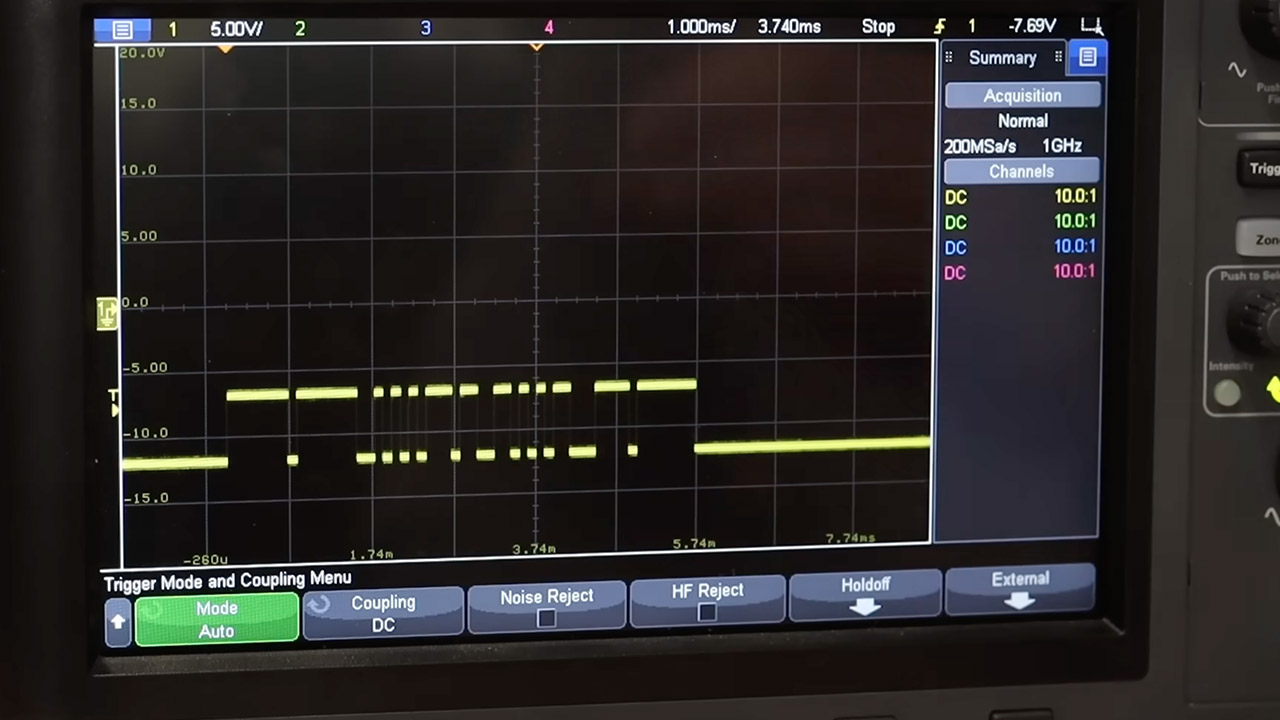

When Dave initially turned on the board stack, the LEDs flashed and one of the RS-485 ports sent out a repeated signal. Hooking it up to an oscilloscope revealed that the data pulses were coming in at roughly 4800 baud, but they were all in a bespoke bit format rather than standard ASCII. Tying in a terminal to take a look yielded nothing coherent. That makes sense, given that the machine was designed to communicate with other industrial equipment rather than humans. After experimenting with the byte order for the big-endian architecture, a few extracted strings from the ROMs occasionally yielded familiar terms such as “address,” “alarms,” and “allowed,” referring to some of the old menu-driven or status-reporting functionalities it used to have.

[Source]