Photo credit: GM

Fifty-six years ago, General Motors dared to do something truly different. They parked a tangerine bubble at a trade-show turntable and asked people to take a good hard look. At Transpo ’72, visitors walked right up to the 512 Electric Experimental, noses just inches from its sleek fiberglass skin, wondering whether this thing was a car, a cockpit, or just some kind of wacky dream on wheels. Standing at a mere 86 inches long, the little GM looked for all the world like a Smart Fort Worth that had been sat upon – but as you looked closer, you could see that every curve was deliberate, every inch carefully thought out.

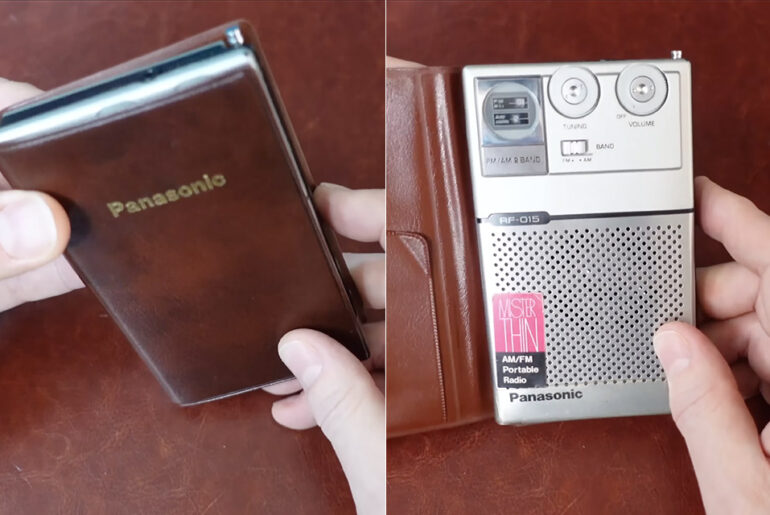

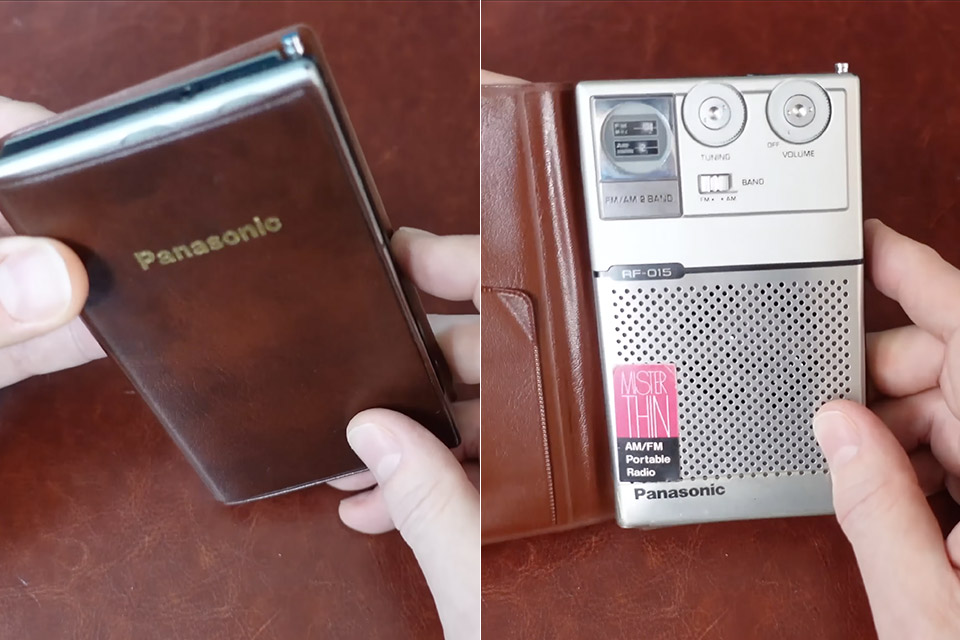

Slide your hand into a 1977 dinner jacket, and you might find a silver cigarette case, a small lighter, or—tucked beside the silk lining—a rectangle barely larger than a deck of cards. When you open the snap, the leather wallet slides open to reveal a radio. Not a toy or a gimmick, but a full-fledged AM/FM receiver from Panasonic named Mister Thin (RF-015).

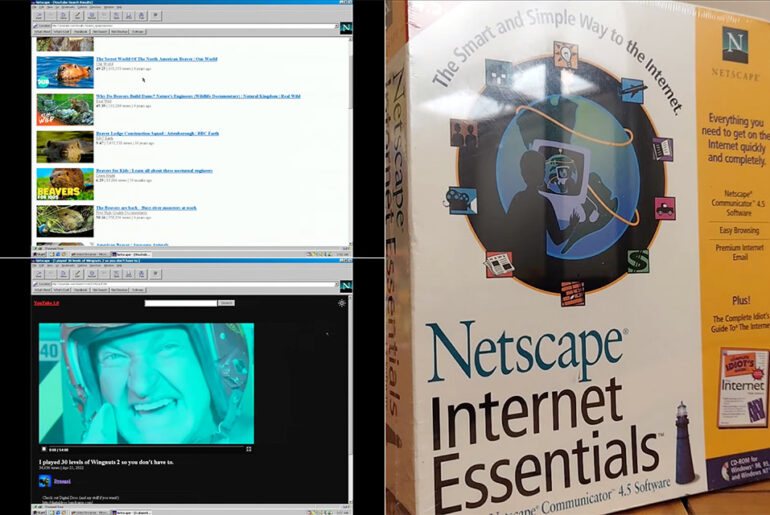

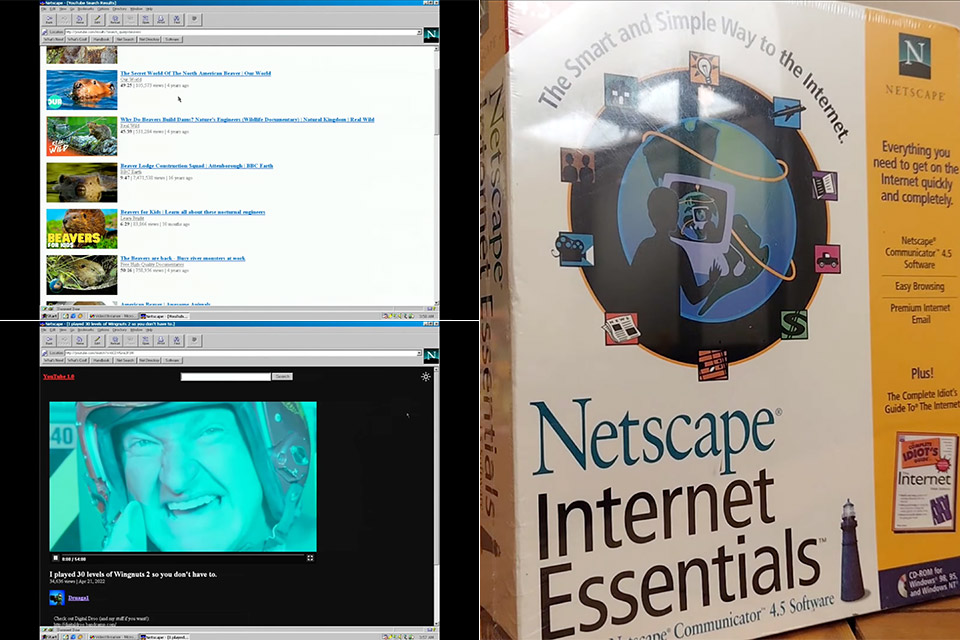

Throaty Mumbo opens a box from the 1990s sealed with packaging tape and pulls out a copy of Netscape Navigator 4.5 that has been shrink wrapped for longer than he has been alive. The plastic wrapping “cracks” like thin ice on a winter pond. Inside, there’s a gleaming CD-ROM, a stack of floppy disks that appear to have been there for decades, and a gigantic 300-page manual that’s thicker than a phone book.

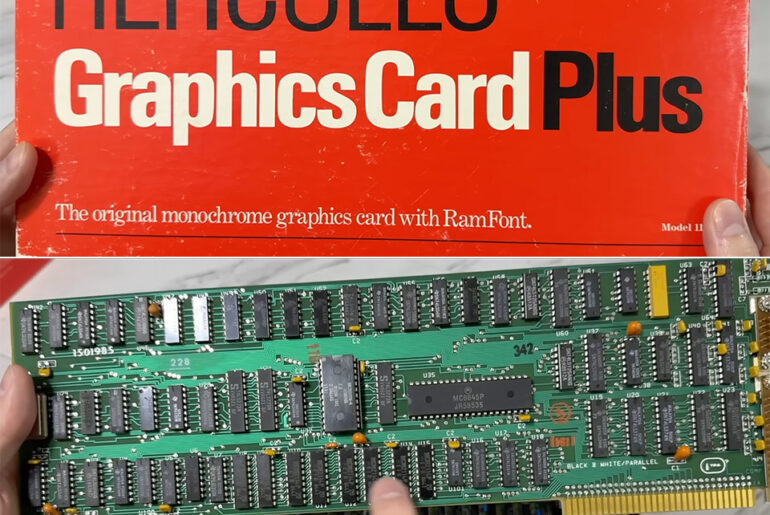

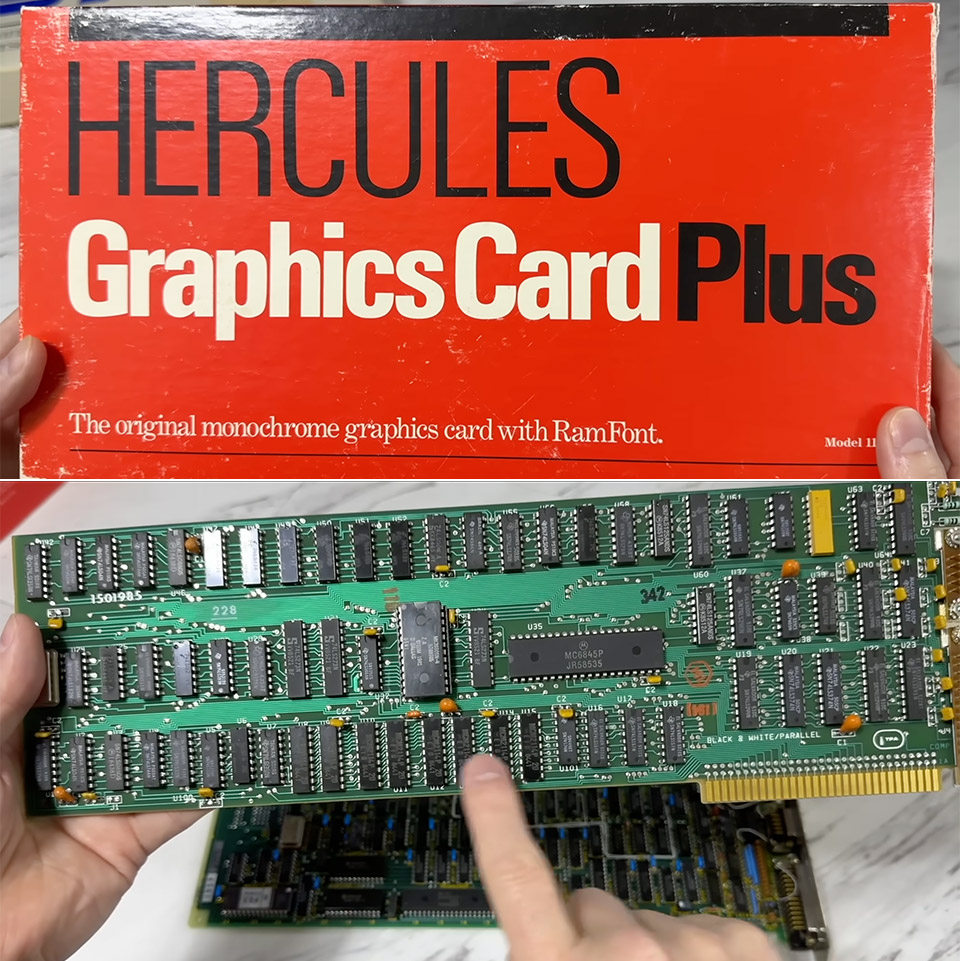

Businesses in the early 1980s were all about paperwork and figures. Spreadsheets were simply rows of figures, documents were heaped up page after page, and IBM PCs were the workhorses that handled all this data, with an option of two monitors. IBM chose Color Graphics Adapter, which provided a splash of color but was only 640 by 200 pixels, making text appear blocky and difficult to read. Then there was the Monochrome Display Adapter, which produced a 720 by 350 pixel screen in a clear green or amber. Hercules Computer Technology identified the gap and stepped in with a card that married both strengths without having to make any sacrifices

In the early 1950s, America was on the cusp of a new era. World War II was fading into memory and the country was full of hope thanks to science and industry. Amidst all this progress General Motors unleashed the 1953 GM Futurliner, the embodiment of the era’s unlimited optimism. This was a 33-foot-long, 30,000 pound rolling billboard for the future, a machine built to wow small town America with tomorrow.

October 18th 1985 was a pretty ordinary autumn day in New York City but the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) was about to start something big – 200 unassuming grey boxes placed alongside cartridges of plumbing adventures on shelves. Four decades later, that simple launch remains the foundation of what we consider entertainment today.

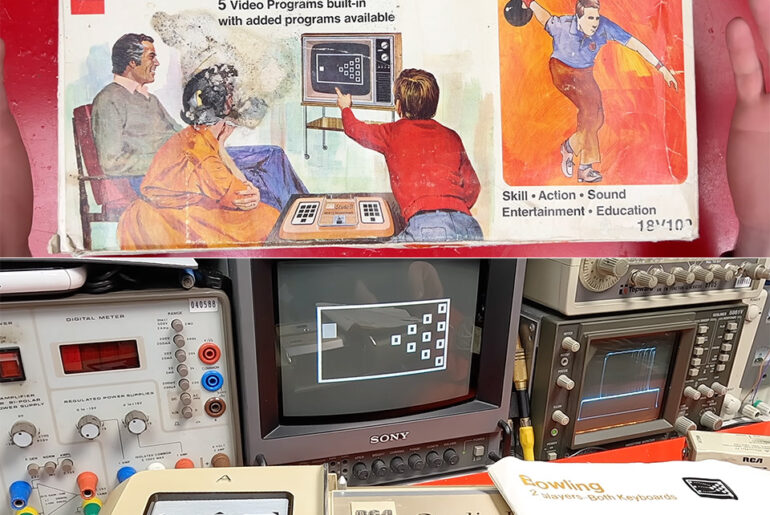

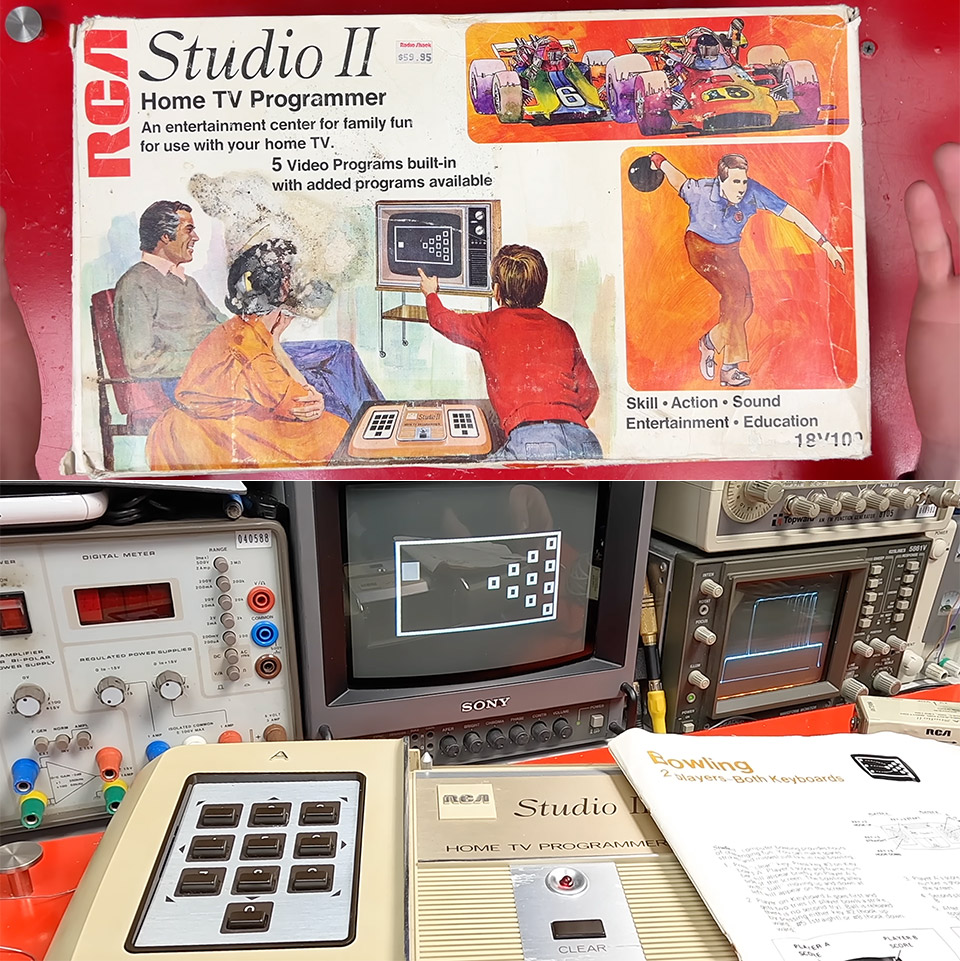

In January 1977, a peculiar box appeared on the shelves of American electronics retailers, marking a company’s attempt to carve out a share of the expanding video game business. RCA, the radio and television behemoth, introduced the Studio II, a home video gaming device that transforms your TV into a “entertainment center for family pleasure.” But within a year, it had vanished, replaced by flashier competitors and relegated to clearance bins.

In October 1976, inside BBC Television Center’s Blue Peter studio, three presenters – Peter Purves, Lesley Judd and John Noakes – gathered around what looked like an ordinary black box. This suitcase-sized device was about to change the way people thought about long distance calls, literally.

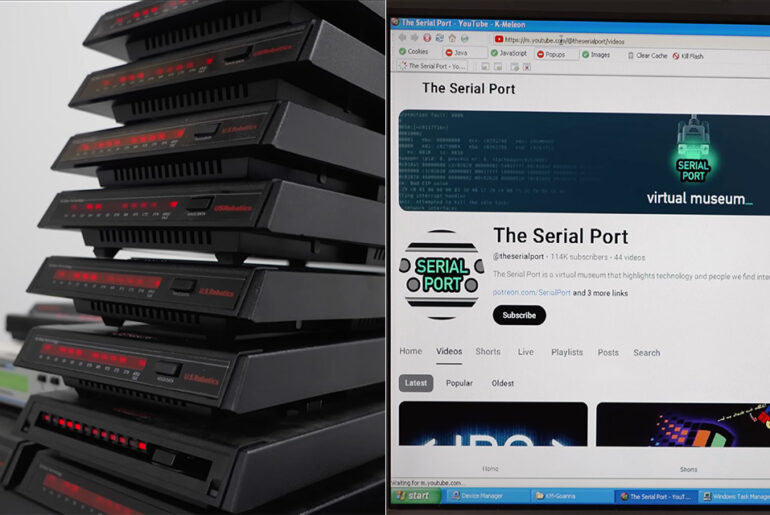

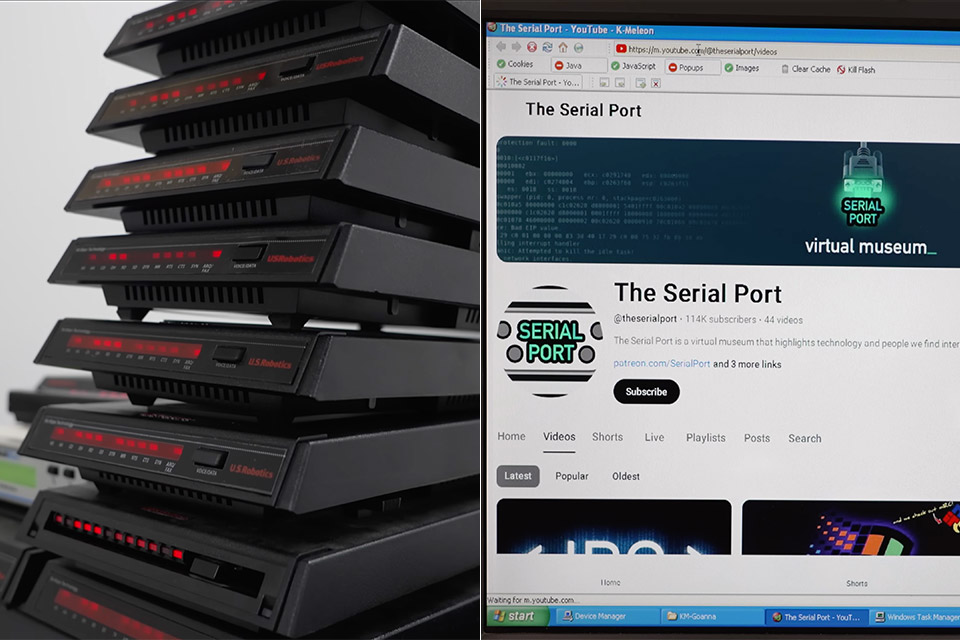

In an age where high-speed internet is as common as water, it’s easy to forget the days when connecting to the internet meant listening to your modem wail like a digital banshee. Dial-up internet, with its slow speeds, seems like a relic of the past. But a group of makers at The Serial Port decided to recreate this old nightmare to…watch a YouTube video via dial-up. Yes, YouTube, the bandwidth-hungry behemoth, is using a connection that can barely load a single webpage.