Photo credit: Carnegie Mellon University

You find yourself in a garden at the perfect time, when the golden hour paints everything in a warm gentle light. A bee hovers annoyingly close to your lens, a tiny speck of pollen clinging to its leg. In the background, a rose blooms in the distance – and then beyond that, a stunning mountain range stretches out to meet the horizon. No matter how good your camera is, even a fancy $10,000 mirrorless beast, you’re always going to have to make some compromises – choose the bee and the mountains will turn into a blur of creamy bokeh. Some have even tried light-field cameras that inevitably sacrifice resolution for a bit of extra versatility. Every one of them is some kind of compromise.

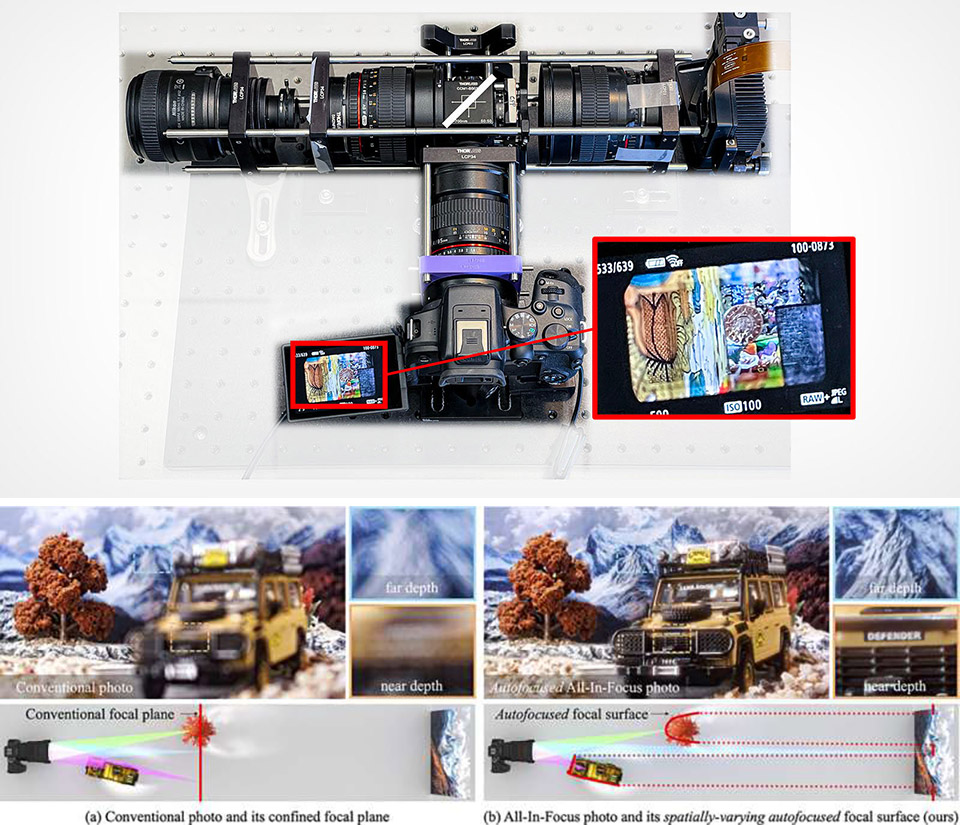

But now, three clever researchers at Carnegie Mellon University have finally come up with a camera that can handle all this in a single shot without any fuss – and with no need for any fiddling in post. They’ve called their magic solution ‘spatially-varying autofocus’ – and honestly its like something straight out of a sci-fi movie, so advanced it makes you think all the lenses that got made in the last 50 years look like the stone age. At the heart of this system is a strange but brilliant optic called the Split-Lohmann lens – its a sort of hybrid of a 1960s varifocal patent and a modern day phase-only spatial light modulator (SLM) – similar to the tech that powers the latest VR displays. Normal lenses bend light in the same way all over the frame, but not the Split-Lohmann. It lets each individual pixel on the sensor focus at a completely different depth.

- Cinematic-Style Footage - Experience the power of Xtra Muse's 1-inch CMOS sensor, capable of recording breathtaking 4K resolution videos at 120fps....

- Ultra-Steady Shooting - No more shaky videos! Xtra Muse's advanced 3-axis gimbal camera stabilizer ensures exceptional smoothness. Enjoy smooth...

- Effortless Framing - Enjoy Xtra Muse's expansive 2-inch touch screen, and switch between horizontal and vertical shooting effortlessly.

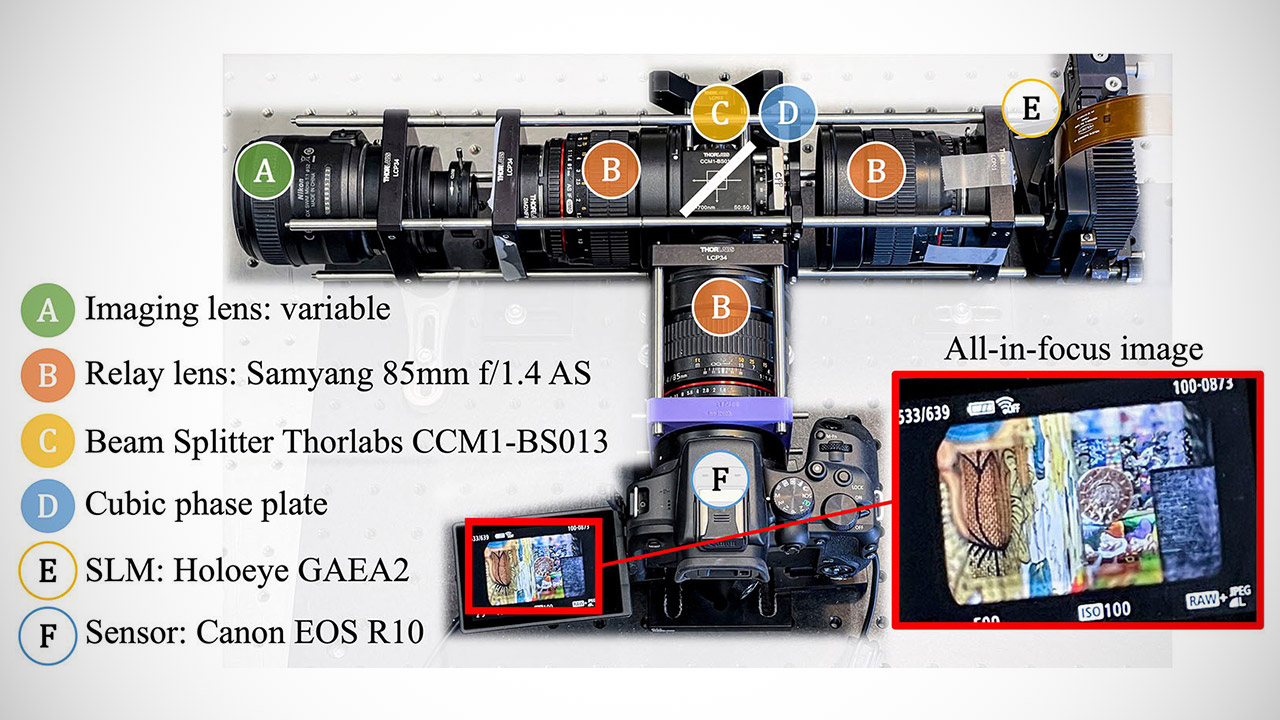

So, how does it perform this magic trick? First, light from the scene passes via a couple of cubic phase plates (yep, lenses shaped like soft cubes), then through a beam splitter, a 4f relay system, and ultimately onto the SLM, a liquid-crystal panel that can tweak light phase with remarkable accuracy. By projecting a carefully worked out ‘phase ramp’ pattern onto the SLM, the camera can bend the focus surface into any old wacky shape it pleases – near objects sharp, far objects sharp, or even a diagonal plane because you’ve got a stair-case in your shot. And it’s all done visually before the photons even reach the sensor.

Of course the lens needs to know where absolutely everything in the scene is, so that’s where the autofocus algorithms come in – two clever variations on technology that probably already lives in your smartphone. First, the cdaf (contrast-detection autofocus) is turbocharged. Instead of trying to find the sharpest bit in a tiny box in the middle of the frame, the camera breaks the image down into loads of tiny super pixels and does a separate focus search on each one – its like each part of the picture has its own teeny-weeny photographer robot. The search is lightning-fast: take three short snapshots at various focus distances, compare the local contrast, reduce the search range, and try again. And it’s all done in a few hundred frames (at most), so the camera has a good understanding of where everything is in the scene.

Second, phase-detection autofocus (PDAF) is based on Canon’s Dual Pixel sensors. Each pixel on the modified Canon EOS R10 used for the prototype has two photodiodes. By analyzing the tiny parallax between them, the system can instantly tell not just if something is out of focus but also which way to correct and by how much. Add that to the Split-Lohmann lens and the camera can focus the whole frame in as few as four frames. That’s fast enough for 21 frames per second video.

Flip through the galleries and your mouth drops as you see a little car in the foreground and a mountain range in the background, both sharp as a tack in the same exposure. A tilting OLED panel of the Arc de Triomphe perfectly in focus from corner to corner despite being at a 45 degree angle. A wire mesh in front of a poster that literally disappears because the camera intentionally defocused only those pixels. These are not Photoshop composites. They’re single RAW files straight out of the camera.

As for resolution, the technology outperforms light-field cameras and focal-sweep approaches and classic focus-stacking (which requires dozens of frames). Modulation transfer function charts – those squiggly lines that make lens reviewers cry – show the Carnegie Mellon prototype delivers sharpness equivalent to a 69-frame focus stack but with fewer frames and no post processing.

[Source]