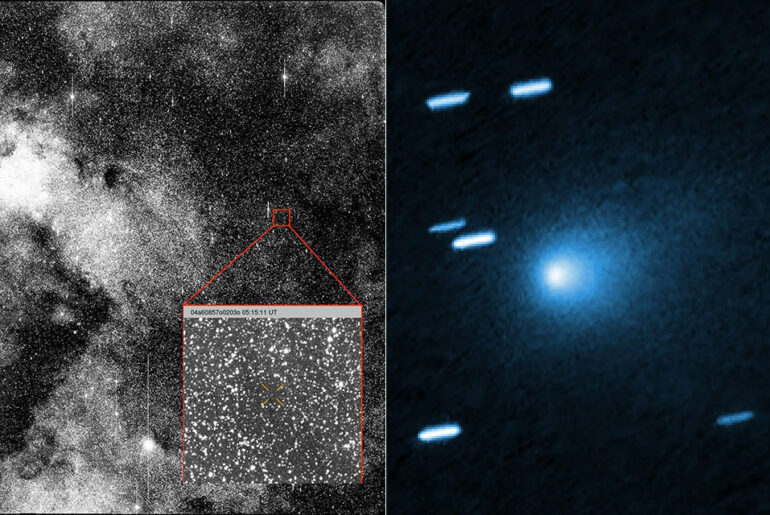

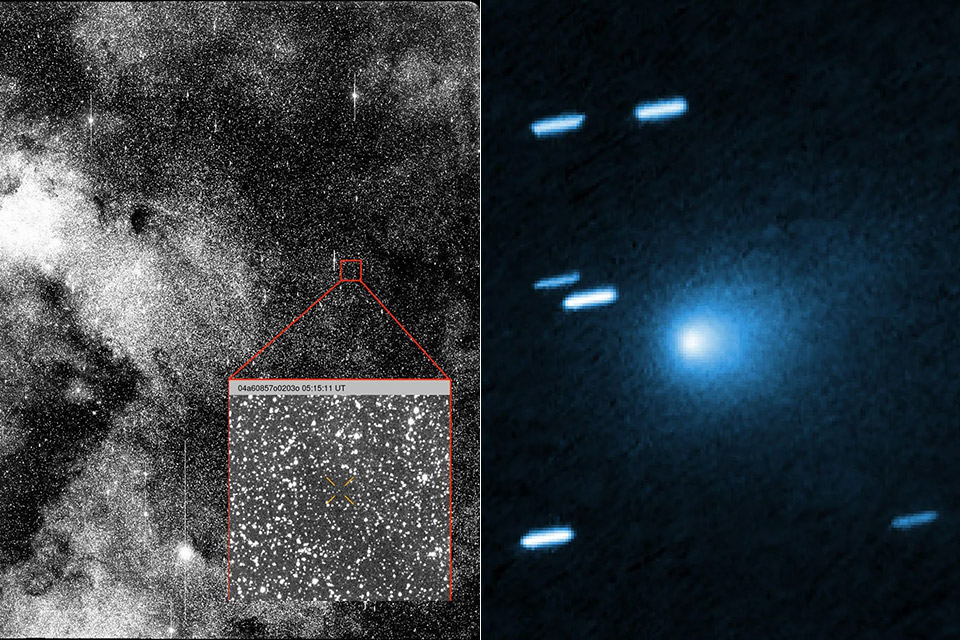

A cosmic wanderer, comet 3I/ATLAS, has entered our solar system and is moving at a whopping 130,000 miles per hour. This interstellar visitor was caught on camera by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope and is the fastest comet ever recorded.

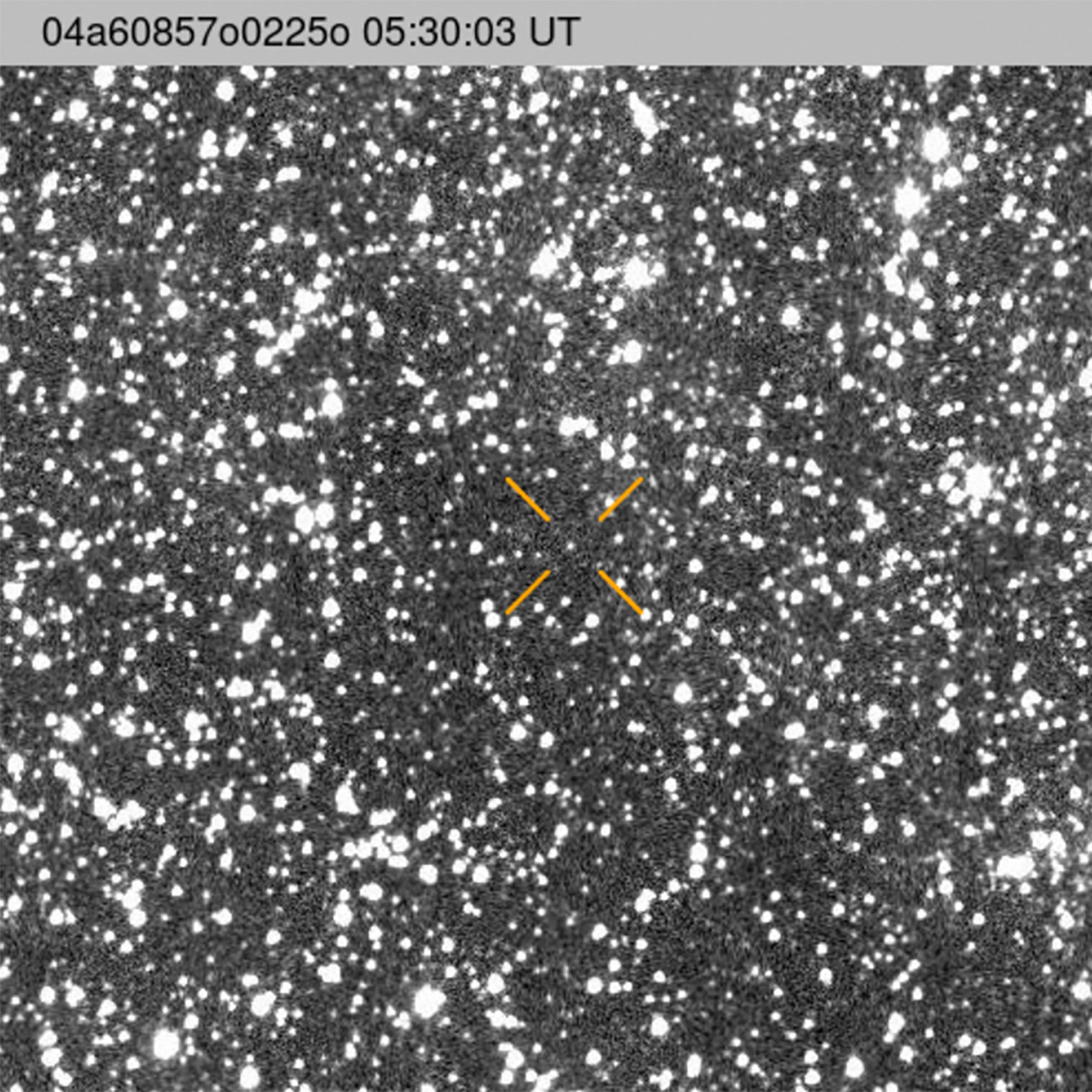

The photo was taken when 3I/ATLAS was 277 million miles from Earth. It shows a blue comet with a faint dust tail and background stars streaking due to the telescope tracking its path. The comet’s nucleus, a solid core of ice and dust, is between 1,000 feet and 3.5 miles across. Nailing down the size of a fast moving object that small from millions of miles away is no easy feat. The dust plume on the Sun-warmed side hints at the comet’s volatile nature as it heats up and turns ice into gas and sheds material in a cosmic dance.

- 2 AVIATION LEGENDS, 1 BUILD – Recreate the iconic Boeing 747 and NASA Space Shuttle Enterprise with the LEGO Icons Shuttle Carrier Aircraft (10360)...

- DEPLOY LANDING GEAR – Turn the dial to extend the massive 18-wheel landing system on your airplane model, just like real flight operations

- AUTHENTIC FEATURES & DETAILS – Remove the tail cone, engines, and landing gear from the NASA shuttle and stow them in the cargo bay during flight

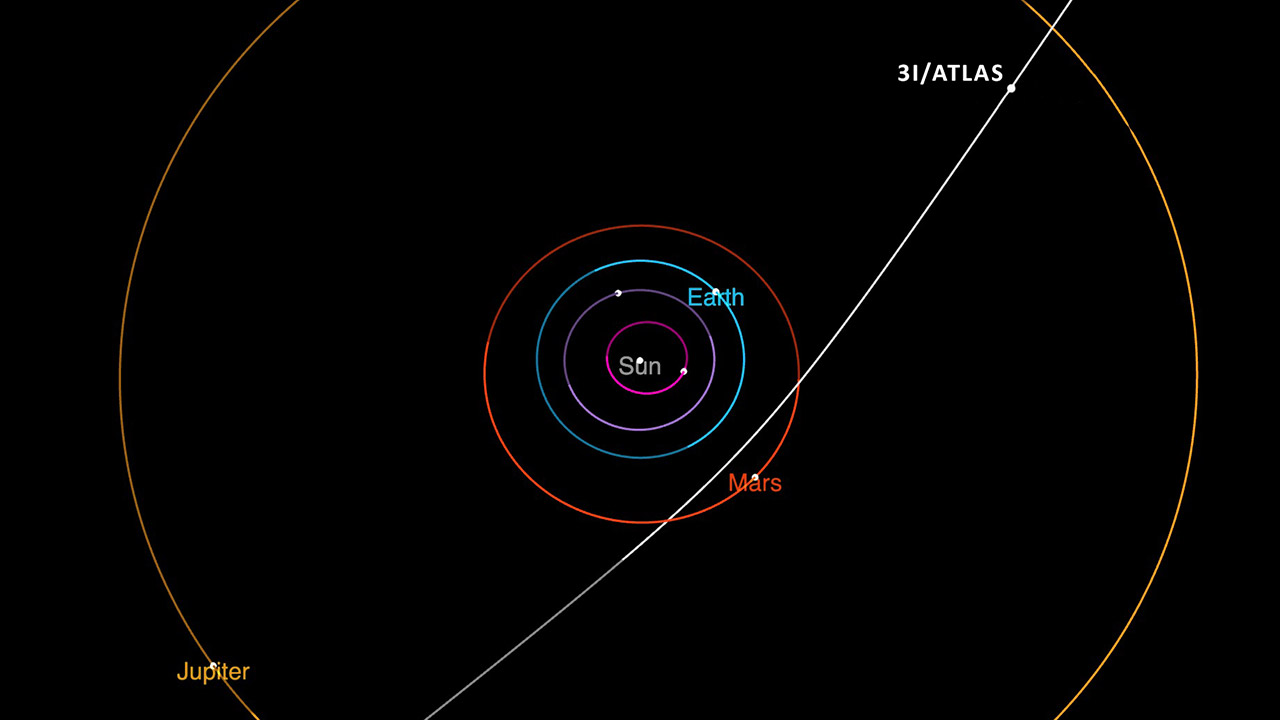

Unlike most comets born in our solar system, this one is from outside, likely ejected from a distant star system billions of years ago. Its hyperbolic orbit (a path that doesn’t go around the Sun but slingshots through) means it’s just passing by and will never return. Astronomers traced its trajectory back to the constellation Sagittarius near the Milky Way’s core but finding its exact birthplace is like finding a needle in a haystack. “It’s like seeing a rifle bullet for a thousandth of a second,” says David Jewitt, lead scientist on the Hubble observations. The comet’s speed means it’s been slingshotting past stars and nebulae for eons.

This interstellar visitor isn’t just fast—it’s a time capsule. Formed in a far-off star system, possibly before Earth existed, 3I/ATLAS carries clues about the early universe. It could have formed in an ice debris ring around a young star or been shattered from a tiny planet ripped apart by the gravity of a white dwarf. NASA’s fleet, including the James Webb Space Telescope and the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, is getting ready to analyze its chemical makeup as it approaches the Sun to learn about the galaxy’s history.

On October 30th, 3I/ATLAS will pass closest to the Sun, about 130 million miles away, just inside Mars’ orbit. At 1.4 astronomical units, it’s no threat to Earth, staying 170 million miles away at its closest approach. But the Sun’s heat might be its undoing. As it gets closer, the intense warmth could vaporize its ices or even break its nucleus apart. If it survives, it’ll zoom back into the void and never encounter another star again. Ground-based telescopes can follow it until September when it gets too close to the Sun’s glare, but it’ll reappear in December for more study.

[Source]