Mark Rober spent years turning backyard experiments into viral social media sensations, from the iconic glitter explosion that foiled package thieves to the mind-bending squirrel mazes that serve as the ultimate obstacle course. His most recent project takes aim at one of the world’s most popular sports. A robotic goalkeeper designed to stand between Cristiano Ronaldo and the net that was inspired from a simple but intriguing question: can engineering prowess defeat athletic genius?

Rober’s experience began in a large field at Wembley Stadium in London, when he took part in a charity match organized by the Sidemen, a group of British YouTubers he had met, and ended with him kicking the ball in front of 90,000 screaming fans. Next thing you know, the ball is in the net. As someone who spent up dreaming of becoming a professional soccer player but lacked the necessary speed and stamina, that moment felt like vindication. However, upon returning to the United States, reality set in. He called his friend Landon Donovan, an American soccer legend with numerous MLS titles and a World Cup bronze medal, to ask what his chances were of getting professional. Donovan gave him a simple training routine: juggle the ball, head it, bend it, launch it deep, and hit a specific target. Rober messed up every step of the way, and his sole reward was penalty laps. The suggestion stung, but it also prompted a shift in approach. If he was never going to be a professional athlete, why not create something that could do the job for him instead?

- FUN FOR FAMILY & FRIENDS: 10 options for friendly competition provide hours of fun for the entire family! Let children battle it out in shuffleboard...

- VERSATILE 10-IN-1 TABLE: Interchangeable table top lets you play slide hockey, foosball, billiards, shuffleboard, table tennis, chess, cards...

- SPACE-SAVING DESIGN: All surfaces can be stacked between the billiard base and foosball table, making it ideal for placement in a child's bedroom or a...

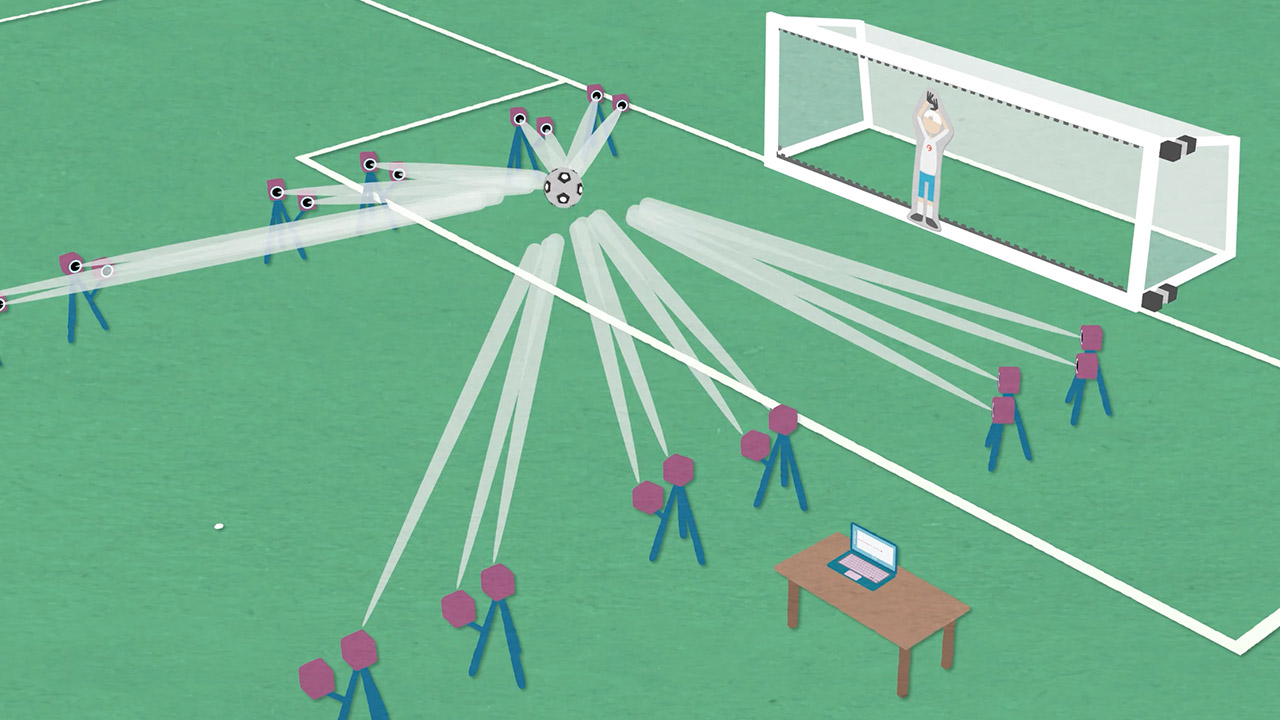

That’s when the robot began to take shape, as Rober drew out a system that needed to react faster than any person could. Soccer balls fired from the penalty spot can reach speeds of up to 80 mph and cover the 12 footer to the goal line in less than a quarter of a second, so the robot had to track that trajectory, predict where the ball would end up, and then slide into position before impact all on its own. The first concepts were simple enough, a basic frame on rails, but things quickly escalated from there. He found 22 high-speed infrared cameras from OptiTrack, each capable of capturing frames at 500 frames per second. Stickers on the ball returned a light signal to those lenses, resulting in a 3D map of the ball’s flight down to the width of a human hair. Then, every six milliseconds, a computer churns through all of that data, feeding predictions to 50 horsepower motors connected to belts. These motors have a lightweight carriage upholstered with carbon fiber and dense foam that can hurtle across the goal mouth at speeds of more than 41 miles per hour.

Data was going to be the key to breaking this nut. Rober gathered a group of the country’s best shooters; after all, having someone who can truly shoot is difficult to quantify. The system easily handled collegiate pros who tossing balls at 40 mph. Then came the high school standouts: Jonah with his straight-line rockets, Tory going for the bends, and Kazushi releasing 55-mph curves. Only a few made it through at first, revealing how far off the trajectory math was, but each miss added thousands of extra data points to the model, considerably improving it.

Xenia, a budding star, hammered one in so hard that the robot snapped straight off at the elbow. Rober simply replaced the arm with a spare, applied industrial adhesive, and increased the foam density a few notches. Neo then came along and began testing the limits with some dipping volleys, while Donald De La Haye (aka Deestroying), the legendary trick-shot artist, blasted 65-mile-per-hour thunderbolts that bent the frame. After a last barrage of shots, Rober had captured over a million frames of motion, more than enough for the AI to begin learning patterns from every angle and spin. Progress was sluggish but steady: against the amateur audience, the save rate had reached 90 percent, and reaction times had dropped to 200 milliseconds. Rober even attempted to incorporate body-language reads for himself, such as a kicker stamping their foot to indicate where the ball was going, but the robot proved capable of handling the basic physics without assistance.

Building this thing became an all-out struggle of trial and error. Rober set up shop in a rented warehouse, and the first testing comprised him shooting balls at a prototype to determine whether it would stand up. One kick at 66 miles per hour sliced open his hand, but it was exactly what he expected; he slapped on a band-aid and continued firing. The cameras worked well in principle, but real balls bend and dip in ways that the basic setup didn’t anticipate. Doubling the camera count fixed the blind spots but created a slew of new problems. The motors moved the frame alright, but heavy shots ripped the padding off the rails like tissue paper…

Rober addressed this by adding shear bolts and a steel crossmember, transforming what was essentially a flimsy stick into something more durable. Power demands increased dramatically. Early prototypes were slow, so he just increased the motors to 250 percent capacity, which is roughly equivalent to running an entire home on a toaster. To make matters worse, there was still the communication issue to resolve; the warehouse had no mobile signal, so forget about transmitting wireless commands halfway through a test. Weeks passed and the robot was still in parts, but it had ultimately shrunk to a tiny ghost of its former existence, weighing less than a gallon of milk yet still able to withstand collisions that would crush a car door like a tin can.