Microsoft’s Project Silica has reached a significant milestone in its goal to develop ultra-long-lasting storage that can survive for generations. Researchers in the field have just published a paper in Nature outlining a major breakthrough in the approach, as they are now using good old-fashioned kitchen cookware glass, such as that found in an oven door or a Pyrex dish, rather than super-specialized glass that is far too expensive for the job.

We’ve seen some interesting demos of the technology in the past. As early as 2019, the team was able to fit a full copy of the 1978 film Superman onto a small piece of quartz glass, demonstrating the feasibility of laser-based encoding in glass. This was a significant event at the time, as it required super-high-purity glass, which was too expensive to use on a broad scale. The original iterations had limited capacity, but the team has consistently pushed the bounds of what is feasible.

- Easily store and access 2TB to content on the go with the Seagate Portable Drive, a USB external hard drive

- Designed to work with Windows or Mac computers, this external hard drive makes backup a snap just drag and drop

- To get set up, connect the portable hard drive to a computer for automatic recognition no software required

The focus has moved to making the technology viable for usage in the real world. By converting to more easily available borosilicate glass, they have reduced costs and made the material more accessible without jeopardizing the ultra-long lifespan. They’ve even conducted tests that indicate data remains stable for more than a century, and they believe it may persist for 10,000 years or more under normal settings. Glass is virtually immune to water, intense heat, dust, and even the harmful magnetic fields that can destroy your conventional hard drive or tape.

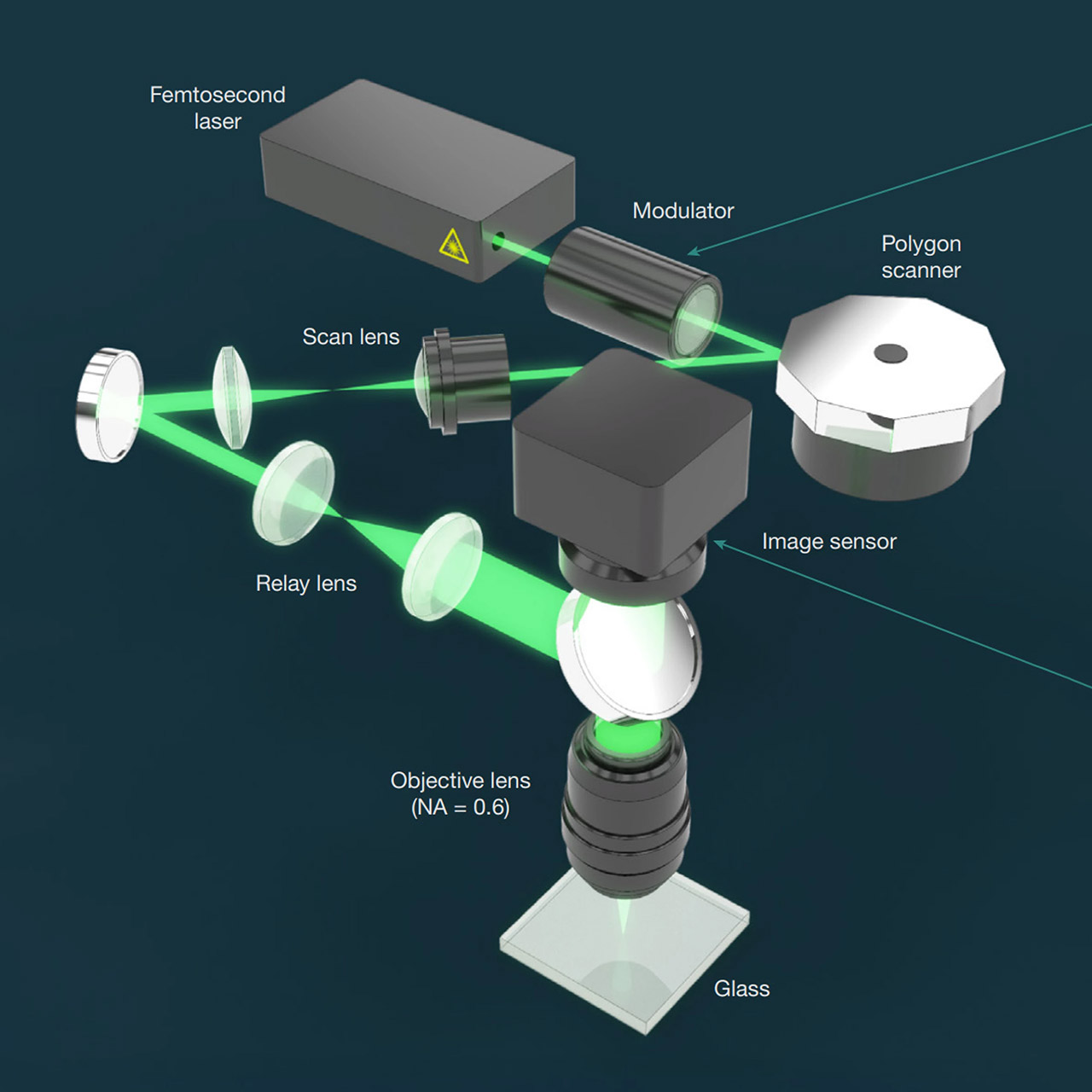

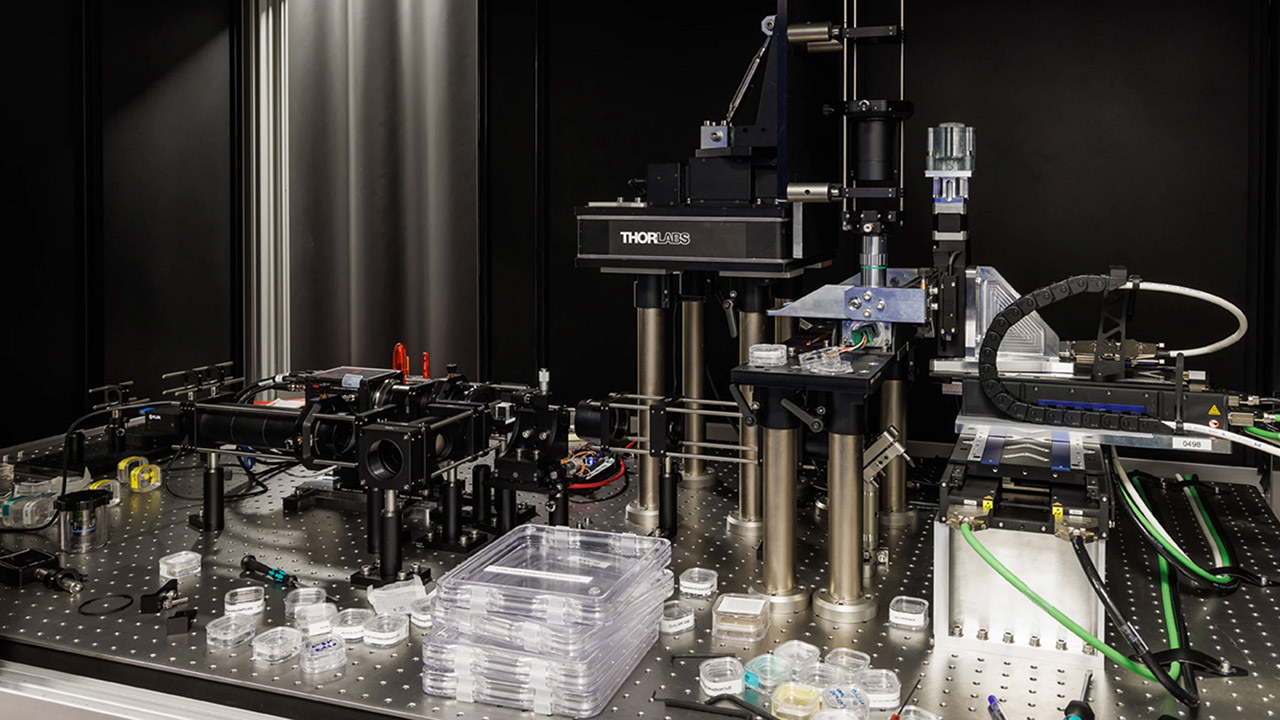

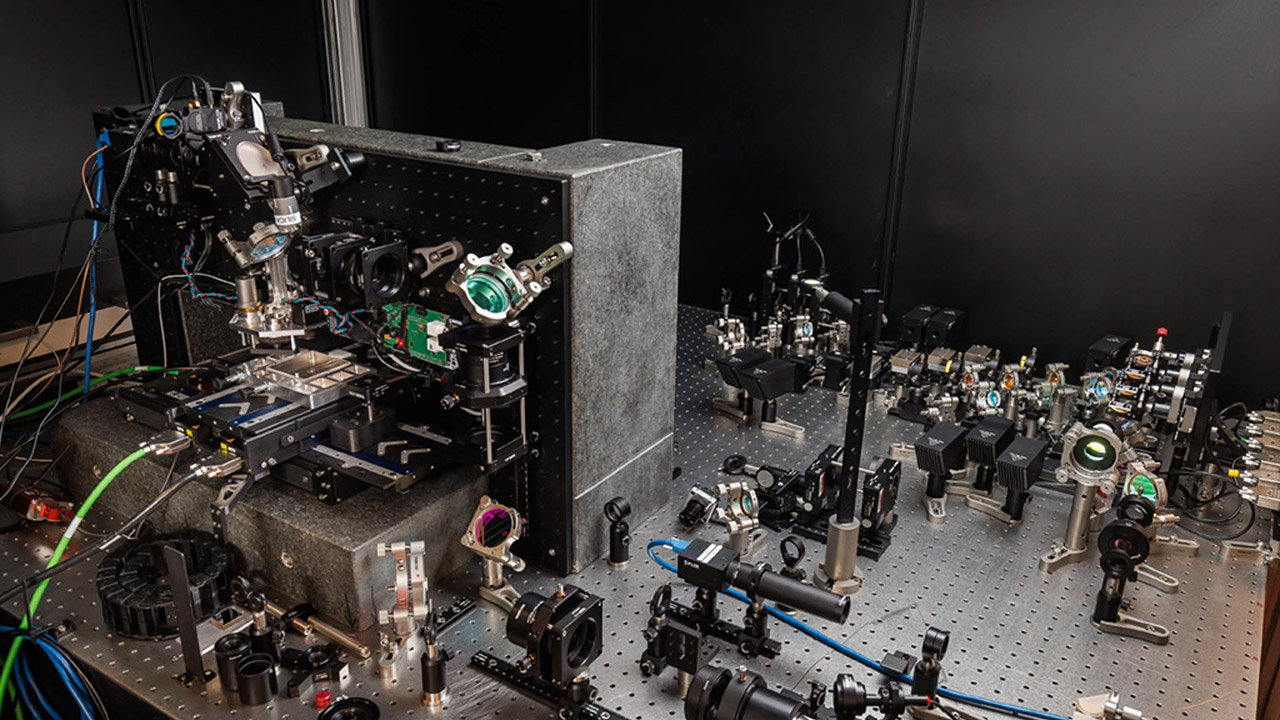

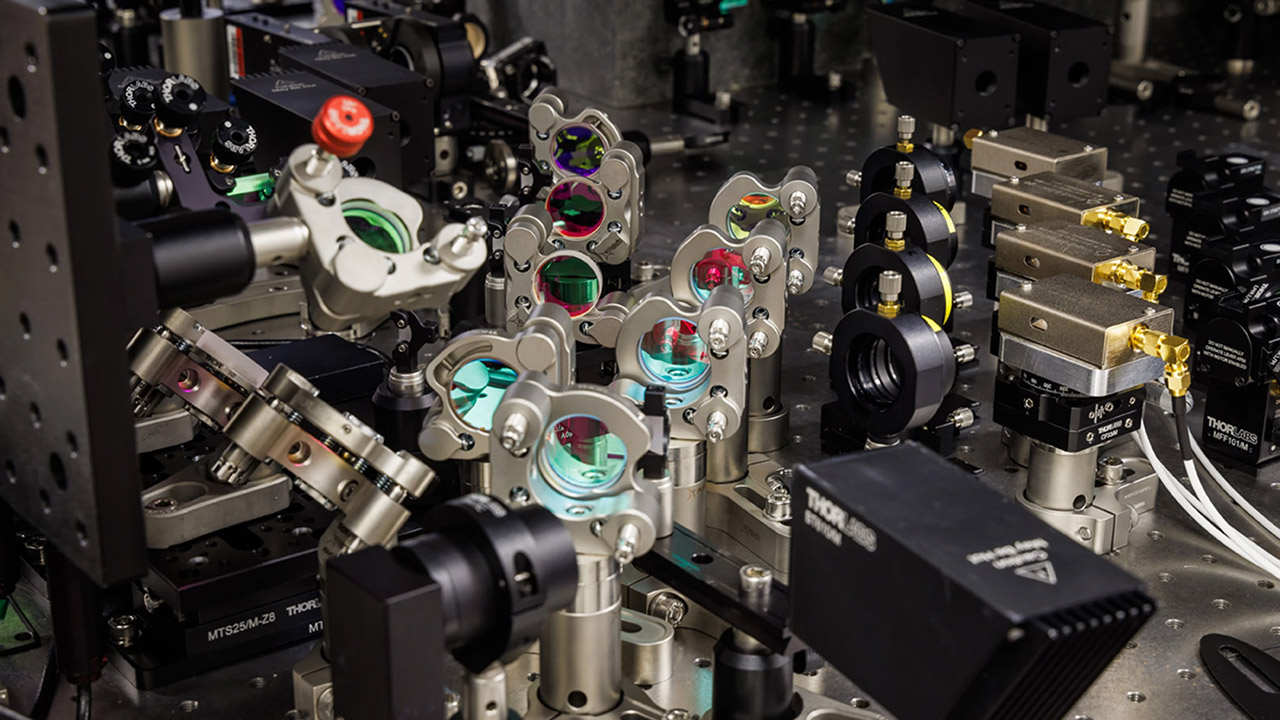

The encoding process is also quite clever, as it involves extremely brief laser pulses to change the glass internally. The new method is far more efficient than the old one; instead of requiring numerous pulses per mark and a rather expensive setup, they can now utilize a single pulse per voxel to get the same effects. This simplifies the technology and speeds up the operation, and they can even write to the glass using many beams in tandem, resulting in a throughput of approximately 18 to 25 megabits per second per beam.

Reading the saved data is also rather straightforward. They only need a single camera to capture the patterns of light passing through the glass, and some sophisticated machine learning to decipher the voxels even when there is some interference from neighboring marks. They’ve also implemented a technique to automatically compensate for faults and calibrate the entire system utilizing natural light flashes emitted during the encoding process.

The current prototype can fit a whopping 2 terabytes of data onto a single 120mm square piece of glass that is only 2 millimeters thick, with hundreds of data layers piled within at once. According to some accounts, they could even obtain up to 4.8 terabytes in similar dimensions, which is really mind-boggling. That equates to thousands of hours of HD video or millions of documents all housed in a nice, small container.

What’s really interesting are the potential uses for this technology. They are not trying to use it for everyday purposes; rather, this is about long-term archiving of critical data. They believe datacenters may use it to dump old files that are rarely accessed, such as scientific datasets, legal records, cultural media, or all of that AI training data they seem to enjoy. They’ve also collaborated with partners to place music archives in harsh locations, as well as a student-led effort to create a “Golden Record 2.0,” encoding various types of music, images, and languages from around the world in the hopes that it will one day be discovered by aliens.

[Source]