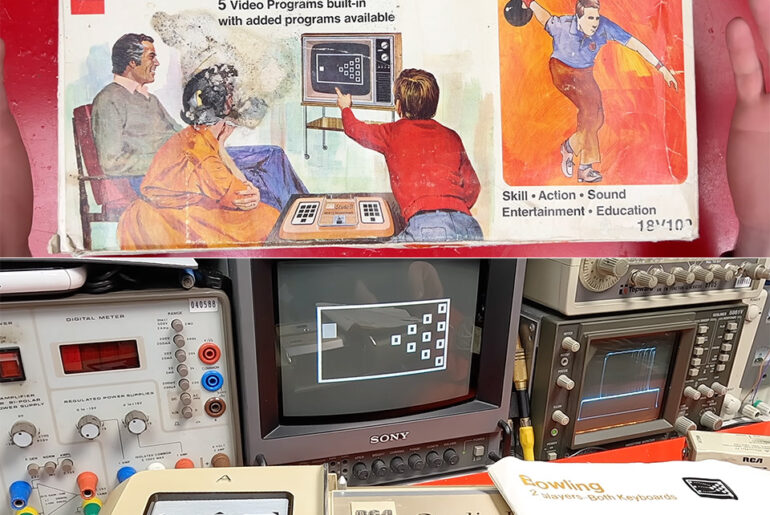

In January 1977, a peculiar box appeared on the shelves of American electronics retailers, marking a company’s attempt to carve out a share of the expanding video game business. RCA, the radio and television behemoth, introduced the Studio II, a home video gaming device that transforms your TV into a “entertainment center for family pleasure.” But within a year, it had vanished, replaced by flashier competitors and relegated to clearance bins.

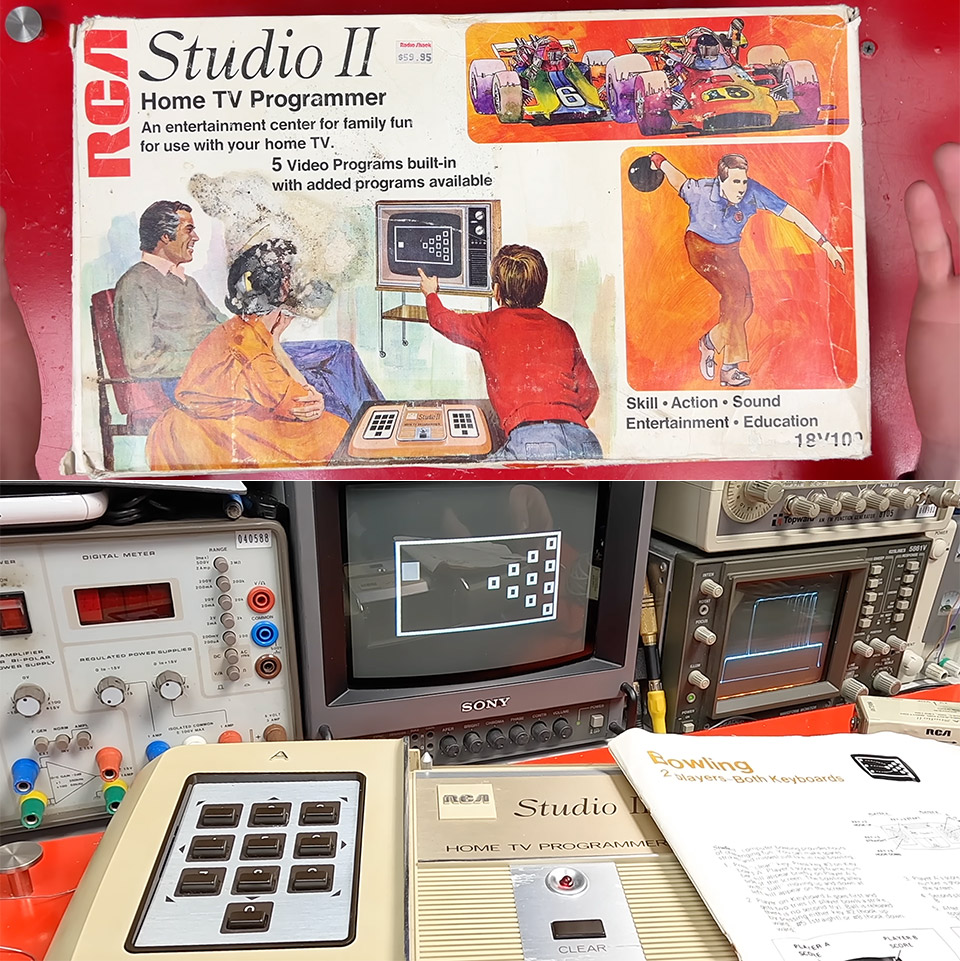

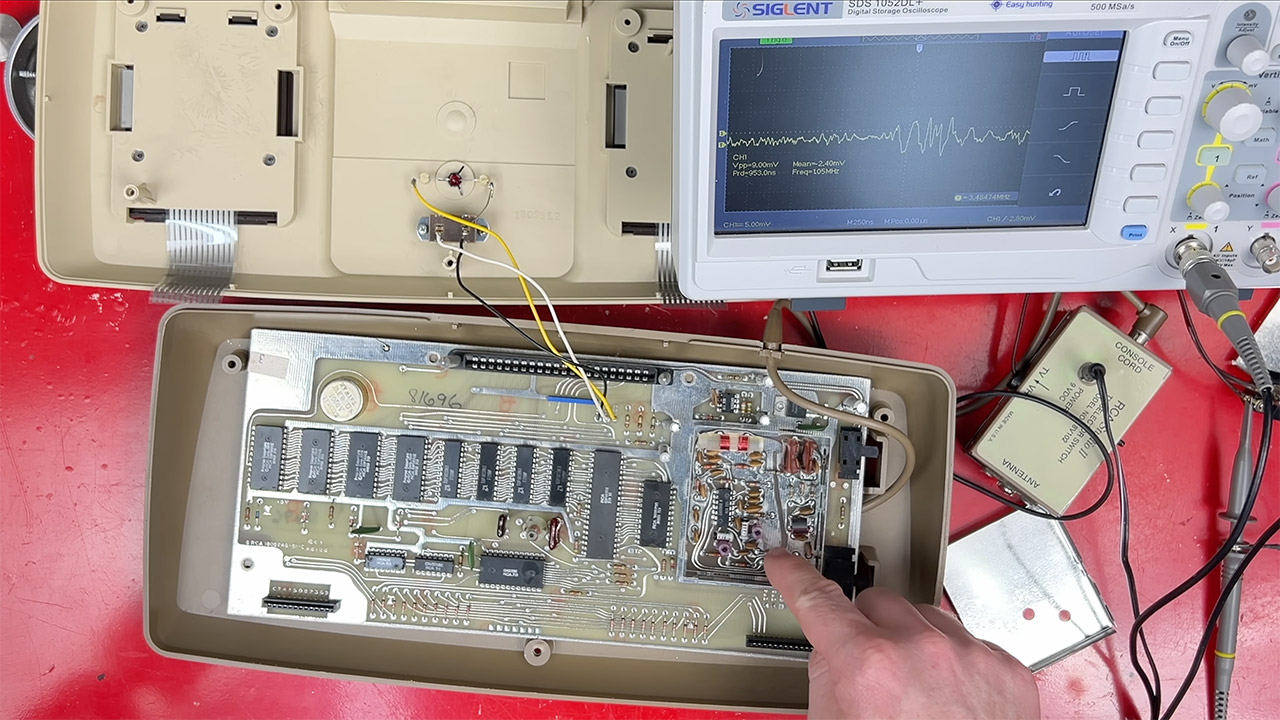

Built from the vision of RCA engineer Joseph Weisbecker, the Studio II came from an unlikely source: a personal computer he built at home in the late 1960s. Weisbecker, a forward thinking innovator, saw the potential of computing in the living room and RCA wanted to diversify so they greenlit his idea. The result was a console powered by the RCA 1802 microprocessor, 1.78 MHz, with 512 bytes of RAM split evenly between display and program functions. The graphics, courtesy of the RCA CDP1861 “Pixie” chip, was a 64×32 monochrome display—black and white squares dancing on the screen. Unlike its competitors, the Studio II shunned joysticks in favor of two built-in ten-button keypads.

- Experience brighter worlds, vivid imagery, and sharper details with 4K gaming and up to 120 FPS that makes everything feel so real it’s unreal.

- Quick Resume: Seamlessly switch between your favorite games and pick up right where you left off.

- Backward compatibility: Play four generations of games, including games that are optimized for Xbox Series X|S to look and play better than ever.

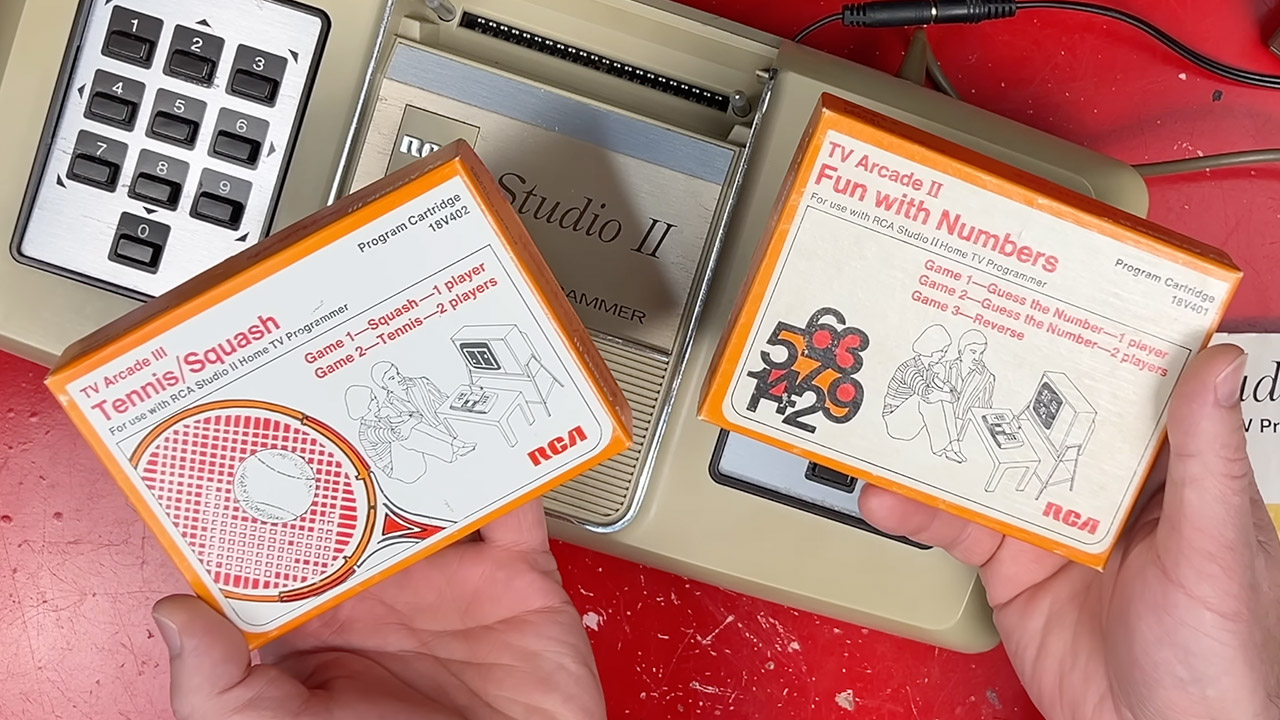

Five games came built in: Addition, Bowling, Doodle, Freeway, and Patterns. These weren’t just games but a showcase of RCA’s attempt to blend entertainment with education. Addition challenged players to add three digit numbers faster than their opponent, a nod to the era’s love of edutainment. Bowling was the graphical heavy hitter, two players could play a game of bowling with limited control over the ball. Freeway was a time trial where players had to dodge a computer controlled car using both keypads for speed and steering. Doodle and Patterns let players draw single pixels or generate evolving designs. Cartridges expanded the library, with 11 released in the United States, including Space War, Baseball, and Tennis/Squash, as well as rarities like TV Bingo, of which only three known copies exist.

RCA’s marketing touted the Studio II as a versatile wonder, a “home TV programmer” that worked on any TV, color or black and white. It had a long 18 foot cord and plug in cartridges, a near first for consoles, but the Fairchild Channel F beat them to market by months and stole the title of first cartridge based system. The Studio II’s cartridges were big and had instructions on the back, simple ROMs that added games like Speedway/Tag, programmed by Joyce Weisbecker, Joseph’s daughter and the first woman to develop a commercial video game. Her School House I, coded in a week in 1976, was a milestone in a male dominated industry.

Despite the innovations, the Studio II flopped out of the gate. Priced at $149 (about $797 in 2025), it had some stiff competition. The Fairchild Channel F was released in 1976 and had color graphics. The Atari 2600 was released in October 1977 and had vibrant graphics and a joystick that felt like an extension of your hand. The Studio II’s monochrome display and clunky keypads looked weak in comparison. Its games were novel but lacked the polish of Atari’s Combat or the arcade flair of Channel F’s titles. Sales were terrible, with RCA estimating 53,000 to 64,000 units sold from February 1977 to January 1978. By Christmas 1977 it was a flop and was discontinued in February 1978. Radio Shack bought up the remaining stock and sold them for $59.95 with a few cartridges thrown in. A bargain for a system that was already obsolete.

The Studio II used a single cable for both video and power, a clever trick that used an RF switchbox with a 3.5mm jack for 9V center-positive power (unusual for the era’s consoles which often used center-negative). Connecting it to modern TVs is a nightmare, often requiring a balun to adapt its 300-ohm twin-lead output to coaxial cable. The console’s graphics were unsynced to its game code and would glitch out, like Bowling’s ball rendering as a rectangle if interrupted mid-draw. Its sound was a series of beeps from an internal speaker and was primitive even for 1977. An AV mod could pipe it to external speakers for slightly less grating effect.